Ford Model A restoration

Posted by Chris Graham on 25th March 2020

Enthusiast Dave Sibbald’s Ford Model A restoration has allowed him to take a step back in time, as Bob Weir discovers.

Ford Model A restoration: The pick-up looks resplendent in its new coat of paint. Although most of the commercials were the heavier, Model AAs, a small number of pick-ups like WS 5100 were produced from the car-based Model A.

For a quarter of a century, Bathgate was home to the BMC/British Leyland factory. The plant opened in 1961, under the management of BMC (British Motor Corporation). During its heyday, it was one of the largest factories in Scotland, building a combination of tractors and trucks. At its peak, around 100 lorries were leaving the assembly line each week, before it finally closed in 1986.

The name D&J Sibbald will be familiar to transport enthusiasts, as it’s been in the haulage business since 1933. The company has used a variety of different lorries over the years, and still owns NSV 491, an Albion KL 127 that was acquired back in the 1930s.

Family firm

“The company was started by my grandfather, John, and his brother, David,” David explained. “The first depot was at Kult Farm, near Whitburn. Back in those days, West Lothian was still dominated by coal mining and shale oil, and the countryside would have been dotted with slag heaps. The brothers moved to Hardhill Farm, in Bathgate, at the end of the Second World War, and their main business was transporting livestock using cattle floats, and this carried on until the early 1990s.”

Before restoration: The Model A needed a lot of renovation work to lick it into shape.

David recalls that, back in the old days, the company used British-made lorries. “In the early years, the fleet was mainly Albions, probably because they were made in Scotland,” he said. “During the 1960s, this changed to Leyland and AEC. With the Leyland factory located in the town, this was an obvious choice.”

But, like many transport companies, the family eventually switched to buying European-made lorries. “A few years ago, we decided to use Scania, and have been with them ever since,” David explained. “We were particularly impressed with Scania’s reliability, particularly over the first 10 years. Unfortunately, the same doesn’t apply to some other manufacturers!”

Fleet news

“As regards our current fleet, we’re using the ‘R’ Series. We also have several Scania eight-wheeled, rigid-frame lorries, equipped with Moffett-mounted fork-lifts. This allows us to deliver goods to sites where off-loading isn’t straightforward. The firm still carries out long-distance haulage, and clients include Saint Gobain and Terex Trucks.”

D&J Sibbald has also been in the news, winning the Scottish Haulage Company of the Year 2018 award at the Transport News Scottish Rewards event. “My father and uncle are still managing the business, and I spend most of my time on commercial vehicle repairs,” said David. “As you might expect, there’s plenty of competition from other transport firms, but we’re currently holding our own.”

David has tried, with the Ford’s restoration, to create a vehicle that’s as close to the original, as possible.

Of course, the modern generation of lorries is a far cry from David’s 1935 Ford A, but he likes the older vehicles. “I remember this particular Ford when I was growing up,” he recalls. “It was owned by an uncle just up the road, in East Calder. He was always talking about restoring the lorry, and even got around to stripping it down to the bare chassis. He told me that the pick-up’s engine was a reconditioned unit that had been fitted by the previous owner. Unfortunately, my uncle also had other projects on the go, and the parts lay around his yard, neglected, for several years.”

According to David, his uncle was the third owner, and the lorry originally belonged to a Mr G Flannigan, who lived a short distance away, in the town of West Calder. “I’ve been told they were a family of travellers, who decided to settle down in West Lothian,” he told me. “Mr Flanigan used the Ford for his rag and bone business, and the lorry was a familiar sight driving around the area.”

Promised to me

“My uncle eventually bought the pick-up and, when I was 15, he said I could have the vehicle when I grew up. Three years later he passed away, and my mother bought the Ford from his estate.”

David collected what remained of the lorry and brought it back to Bathgate. “I was still a teenager, so the Ford was stored away in the company garage,” he said. “Things stayed that way for many years, until 2014, when I decided to see if the engine and gearbox still worked. We put the engine on a pallet, and soon had it up and running. Unfortunately, I also got distracted, and this was as far as the project went at that stage. This lasted until 2018, when we finally decided to give the lorry’s restoration the green light.”

It wasn’t until 2018 that the lorry’s restoration was finally given the green light.

David was fortunate in that he was about to get some help from an unexpected quarter. “I’d actually got around to sorting out a workspace, stripping the axles, brakes and suspension, and cleaning all the parts, when I bumped into Kenny Livingston,” he recalls. “Kenny had just retired and was at a bit of a loose end. One thing led to another, and he agreed to help with the resto.”

Mr Livingston was true to his word, and spent the best part of nine months working on the Ford. “Kenny was around at our depot every day except Thursdays,” David recalls. “He even did the woodwork for the tail board, which is made from Meranti; a hardwood that’s grown in the Far East.

We’d visited some local suppliers to see what was available, and I’d considered using either oak or ash. But getting hold of the right quantity would have been more expensive, and held up the project, so Meranti seemed an adequate replacement, so we opted for that.”

David ended up using all the parts that would have been fitted to the original lorry, except for a pair of rear wings.

Such valuable help

“Fortunately, David still had one of the lorry sides, so they were able to make an accurate replacement. “Kenny even used some of the metalwork from the old tailboard, and bent it into shape,” he said. “If it hadn’t been for his help, the restoration would still be just another ‘work in progress.’”

David had expected to have difficulties tracking down spare parts for the 1930s lorry, but was pleasantly surprised. “I suppose that was one of the advantages of choosing to restore a Ford, as against another make of vehicle,” he explained. “A few parts had been mislaid over the years but, despite the Model A’s age, many of the necessary replacements were still available. For most of the stuff we used O’Neill Vintage Ford, based in Coalville, Leicestershire. Every time I put in an order, the parts usually arrived the following day.”

David also recalls he was prepared to travel some distance to get his hands on the right spares. “O’Neill’s were very helpful, but we were still short of a few items,” he recalls. “For example, we had an awful job getting cups for the back springs. I was eventually put on to another enthusiast, John Charlton, based in Lowestoft. I decided, on the spur of the moment, to borrow the company’s van and drive down to Suffolk.

“I remember my father spotted me on the way out of our yard and asked me where I was going. I replied I was visiting a supplier the other side of Carlisle, which was a bit of an understatement! It was a long journey, but John was very helpful and, apart from the much-needed spares, also gave me a lot of useful advice.”

Maximum originality

David has tried, with the Ford’s restoration, to create a vehicle that’s as close to the original, as possible. “WS 5100 is a 1-ton pick-up based on the Model A saloon car,” he said. “Ford also produced a heavier commercial vehicle, called the AA, but that’s a slightly different model. The commercial versions of the Model A used the same parts as the car versions, except for the back axle. The front axle is like the car’s, apart from an extended hub which gives the lorry the extra width.”

The finished Ford has already jogged a few memories, including with David’s mother!

David ended up using all the parts that would have been fitted to the original lorry, except for a pair of rear wings. “John Charlton supplied me with a pair of authentic, Model A wings, but I decided not to fit them because they look terrible,” he laughed. “The spread of the wheel seems a little excessive, and the wings look like they were added as a bit of an afterthought.”

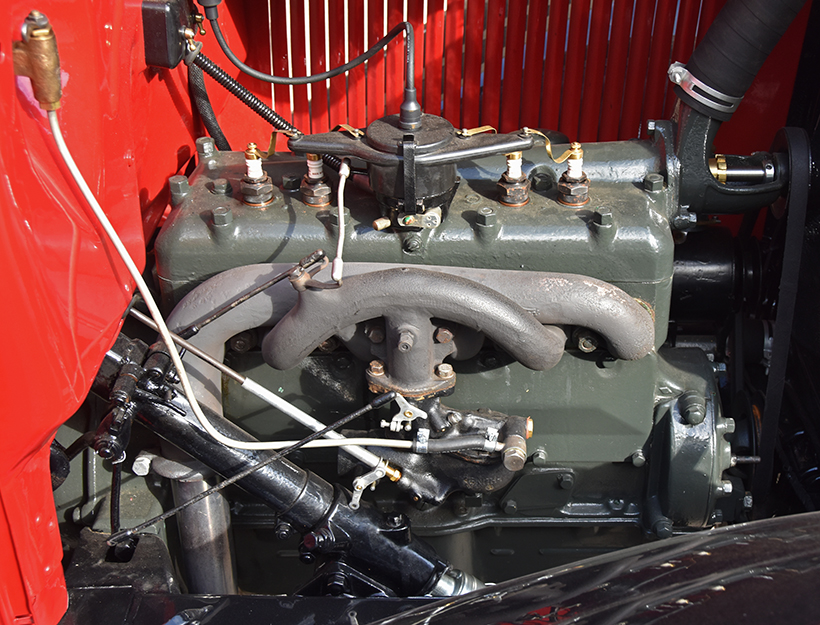

While Kenny concentrated on the chassis, David spent a lot of time sorting out the mechanics. “I’d already stripped the reconditioned engine down to the bare block,” he recalls. “I then took all the parts to Jem Engineering, in Falkirk. They reset and fitted unleaded valve seats, so the engine can run on modern-day fuels. Most of the parts were still in good condition, and the engine runs OK.”

The woodwork is all new, and was made by David’s friend, Kenny Livingston. Interestingly, the Soviet company, GAZ, made a commercial version of the Model A under license, between 1932 and 1936.

The day finally arrived when David could get behind the steering wheel for a test drive. Although he’d never driven a vehicle quite like the Model A, he said it was an interesting experience. “Given the Ford’s age, it’s not too bad,” he told me. “I’m a big guy, so the cab is a little cramped. The controls are a bit unusual, because the throttle pedal is in the middle of the floor. There’s also an advance and retard hand lever for the distributor. In practice, you adjust this depending on your speed. In later vehicles, this would have been done automatically.”

DVLA dealings

Now that the Ford was roadworthy, David had to get the pick-up registered with DVLA, in Swansea. “When I’d originally taken custody of the Ford, one of the boxes contained a second engine,” he said. “I didn’t think much about it at the time, as my uncle was always messing around with different vehicles. I assumed it was just another old engine, and decided to hang on to it for the time being.”

The cab is a mixture of old and new, and certainly looks the part. Instruments were minimal, but some might say this is a blessing in disguise!

David then discovered that this engine was, in fact, the Model A’s original, factory-fitted unit. “WS 5100 was still on the DVLA website, listed as a 1935 Ford Model A lorry,” he recalls. “I sent off for my V5, and included a covering letter that basically said these lorries had come out the factory without a chassis number. I got a reply from the DVLA saying that the engine number amounted to the same thing.

“I was then faced with a problem as the Ford was fitted with the re-conditioned engine, and this obviously had a different serial number. As far as I knew, the transaction had been a straight swap for the original engine, as this would have been normal practice at the time. Without the original paperwork, there was no way of knowing that number.”

According to David, the reconditioned engine is from the later B-Series.

Engine revelation

“Just out of curiosity, I decided to check the other engine for identifying marks, and spotted what looked like a Model A number stamped into the metal. I still hadn’t made the connection with the Ford, but decided to take a chance and use this number instead. Much to my surprise, the DVLA wrote back and said that the number tallied with the number listed on its records. In other words, the second engine was in fact WS 5100’s original engine! It hadn’t occurred to me all these years later but, if I’d known, I would have probably used this engine in the lorry’s restoration, instead.”

David says the foot controls – with the throttle pedal in the middle – took a bit of getting used to.

Once the body and mechanics had been restored, David set about refurbishing the cab and applying the signwriting. “The leather seats were made by a local supplier,” he explained. “I also arranged to have the lorry finished in its original ‘G Flannigan’ colours. I had a hunch that once older enthusiasts saw the lorry at shows, it would jog a few memories.”

This turned out to be a shrewd move, as David has already been approached by people who can remember the lorry driving around West Calder. “My mother even remembered the Ford from back in the days when she was a little girl,” David added. “It used to drive around the streets handing out balloons and other cheap toys to kids in return for old clothing. One of the Flanigan family is still alive, and told me that the lorry was originally bought at the old Alexander commercial vehicle dealership, in Edinburgh, for £167. This sounds like a bargain in today’s money. Now that the lorry has been restored, I suppose you could say it’s a piece of living history.”

David Sibbald with his fully-restored, 1935 Ford A.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FORD MODEL A

The Ford Models A and AA were replacements for Henry Ford’s legendary Model T and TT. Development started in 1926, and was completed the following year.

The new models’ body was outsourced to various manufacturers, including well-known Detroit coachbuilders Briggs & Murray. They shared many things in common, although the commercial model had a more workman-like interior. The chassis was also made substantially larger, to carry commercial loads.

The A was powered by a 3.3-litre petrol engine producing 40hp at 2,200rpm, and was fitted with a Zenith carburettor. The engine was driven through a three-speed, manual floor shift, and equipped with an up-draft carburettor, six-volt generator, two-blade fan, mechanical water and oil pumps, electric starter and four-row radiator. The model was also the first car to use safety glass for the windscreen. The vehicle was available in a variety of designs, including saloons, coupes, roadsters and commercials.

The dominance of Ford’s new car meant that it accounted for a staggering 40% of total US sales, and the launch date on December 2nd, 1927, was a major event. People turned out in their thousands to get a glimpse of the new car, and 30,000 orders were taken in New York alone on the first day. Production of the car finished in March 1932, but commercials were available until 1936.

You can subscribe to Heritage Commercials magazine by clicking here