Richard Hornsby traction engine

Posted by Chris Graham on 11th April 2020

Bob Butrim recounts the history and restoration story of Mark Leahy’s fine, 1890 Richard Hornsby traction engine in Australia.

Photographs courtesy of Mark Leahy

Mark Leahy’s fine, 1890 Richard Hornsby traction engine (No 7089) during its first test run, in August 2017.

No sooner had Mark Leahy completed the virtually single-handed, 17-year restoration of his 1917 Foden wagon (No.7581), he jumped straight into what he imagined would be a relatively quick project; the restoration of an 8hp, single-cylinder traction engine – Richard Hornsby, No 7089, which had left Lincoln, England, on May 25th, 1890.

These days, Mark’s a pressure vessel and plant inspector working a month-on, month-off shift pattern in the oil fields of New Guinea. This means he’s at home in Ballarat, in the state of Victoria, Australia, every second month, where he’s most often to be found in his small workshop. Mark has a particular interest in Ruston, Proctor products – owning, among other things, one of the few three-speed Ruston, Proctor road locomotives in Australia (No. 48113, which was dispatched from Lincoln on November 19th, 1913). It was probably this interest, and the later association of Ruston, Proctor with Richard Hornsby & Co., that attracted him to Hornsby traction engine No 7089.

Tasmanian import

This engine was imported to Tasmania through the agency of AG Webster & Sons, of Hobart, which then held the Tasmanian Hornsby agency. The Australian mainland agency was held by BK Morton, at that time. The Webster agency for Hornsby was relatively short-lived, starting in about 1887 and lasting only until 1891, when it transferred its allegiance to Marshalls of Gainsborough and, in so doing, created a wonderful market for this firm’s products that was to continue until the late 1930s.

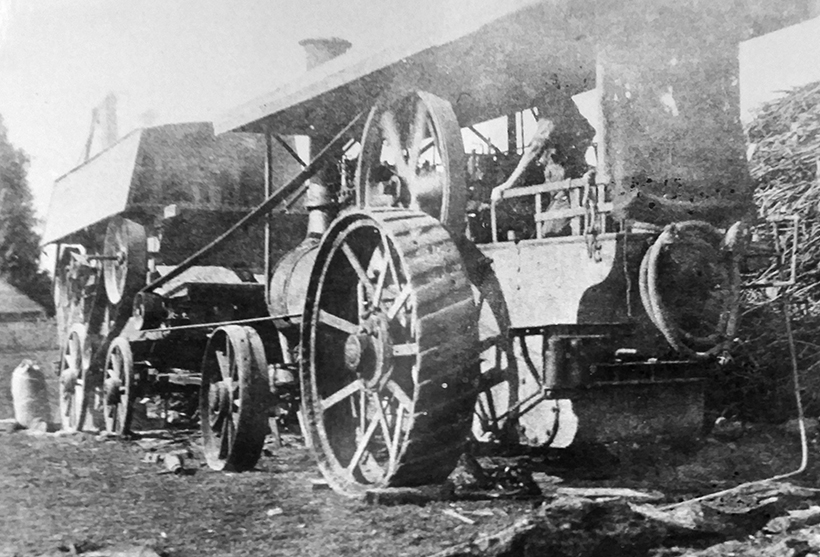

The engine in use in the 1890s at Strathmore, Tasmania, carting wool for James Boyes.

During the period that Webster’s had the Hornsby agency, it sold about 40 portable engines, but only a handful of traction engines; just three of which were of 8hp units. These 8hp engines were acquired for a specific task since, in addition to their normal roles of threshing, chaff-cutting and haulage, they were sold for direct ploughing in an attempt to introduce mechanisation to this job in Tasmania. Special Hornsby ploughs, classed as ‘CYYY’, with three and five furrows, together with ‘self-lifting and steering arrangements’, were sold together with the engines, for this specific purpose.

Webster’s Tasmanian Agricultural & Machinery Gazette published glowing reports of six acres being ploughed in a day, to a width of 12in and a depth of six inches. In reality, the plant was only successful in ideal conditions. In the wet, the engines would bog-down badly while, when it was very dry, the 8hp singles weren’t powerful enough to do a good job. What’s more, when working hard, their sharp exhaust provided a very real fire risk in the Tasmanian bush land. The experiment was soon abandoned, and the engines went back to being used for their normal traction engine tasks, although a few farmers persisted in using them for direct ploughing for several more years.

Making the news

The Tasmanian newspaper reported, on Saturday, May 4th, 1895, that Mr W Gatenby of Woodburne, Cressy, had purchased an 8hp Hornsby steam ploughing plant, second-hand, and was doing his summer ploughing at a speed of one-and-a-half miles an hour. The newspaper report went on: ‘It is claimed that, in the height of summer, some forty or fifty acres of fallow can be ploughed per week and, in the second ploughing, even more than that number can be turned over.’ Perhaps, not surprisingly, no more is heard of this attempt and, presumably, the engine was returned to other, normal duties.

The Hornsby engine photographed – possibly – in the 1930s, towards the end of its working days for Morey at Swansea, in Tasmania.

Not long after the last of Webster’s glowing reports in 1891 on steam ploughing, the firm gave up its agency in favour of Marshall’s. BK Morton sold another couple of Hornsby traction engines in Tasmania, including another 8hp single – No 7297 – which worked for Ed Hobbs at Ulverstone, on Tasmania’s north coast, before being sold to WJ Tucker of Derby and, subsequently, to RG Arnold, in 1930. Following some time spent in a playground, this engine returned to England during the 1980s, and is now to be found – named Bob – at Village Church Farm in Skegness, Lincolnshire.

Hornsby No 7089 was sold new to James Boyes of Strathmore. in north-east Tasmania. He placed the engine under the control of Mr H Mohr, of nearby Longford, and it was used for local contract work, in addition to the work required by its owner. The area of operation around Longford was – and still is – good, agricultural land that’s particularly suited for cultivation; in particular, grain crops. As a result of this, a Hornsby threshing machine with a five-foot-wide drum, was provided to work with the engine.

Multiple uses

The Colonist newspaper, on Saturday January 24, 1891, reported that the engine was: ‘the first complete plant of its kind which has been imported and, in addition to threshing, can be used for log hauling, ploughing, carting on roads, and so on.’ An interesting photograph of it at that time shows it hauling bales of Boyes’ own wool, loaded on horse wagons. The engine appears to have been subsequently condemned by the boiler inspector and, in 1913, was sent to Glasgow Engineering in Launceston, to have the original iron boiler replaced by a new steel one. At about this time, it was sold to a near neighbor – Mr Armstrong, at Longford – who soon sold it on to Frank Morey at Swansea, on the east coast of Tasmania. He was a well-known threshing contractor in that area who had a number of threshing sets in operation.

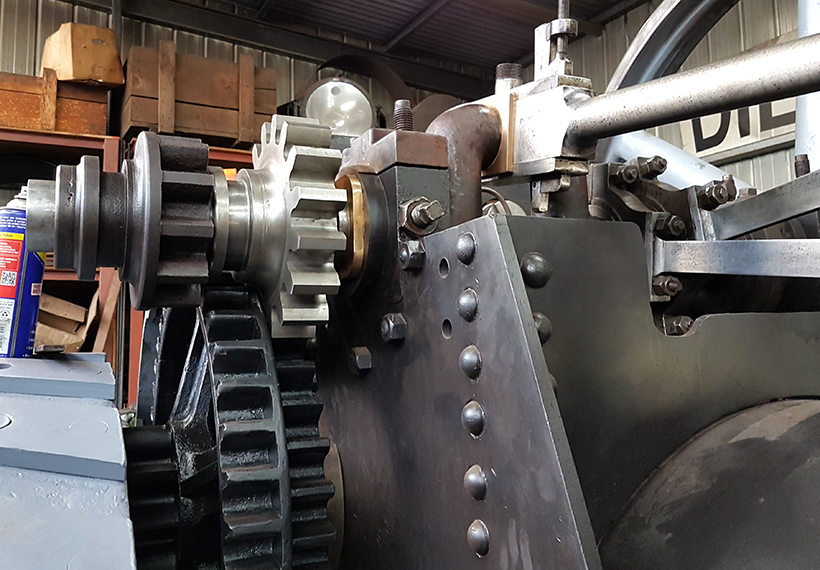

By the 1930s, the Hornsby was out of use and has deteriorated into a semi-derelict condition. However, a shortage of fuel and motive power in the early days of World War Two, apparently saw an attempt by local government officials to return the Hornsby to work but, after a start was made – including the manufacture of some new gearing – it was found that the boiler work required to make the engine serviceable, didn’t warrant its repair.

Hornsby No 7089 in storage at the writer’s premises, and as acquired by Mark Leahy in 2014.

Thus, the Hornsby reverted to its semi-derelict condition, and continued to deteriorate until, eventually, it was acquired for restoration in the 1970s. However, the renovation plans were again abandoned due to the proposed expense of the necessary boiler repairs. Then, after another change of owner, the engine ended up in the joint ownership of Bruce Roberts and the author who, at the time, were looking for an appropriate machine to drive their Barford & Perkins ‘roundabout’ ploughing tackle, then under restoration.

Unsuitable application

As things were to turned out, it was soon discovered that the Hornsby single-cylinder engine was going to cause problems with the roundabout tackle, as it wasn’t suitable for the work, a twin-cylindered engine being needed for that task. As a result, the restoration project went on to the back burner, and the engine was moved to languish at the back of the workshop.

Mark Leahy had often seen the old, three-shaft Hornsby in the workshop over the years during the time that he’d been pestering with regard to the Foden wagon mentioned at the start, and was quite taken by the engine. As it happened, Bruce and I had decided several years previously that when the time came, the engine would be passed on to Mark.

Then fate stepped in and, somewhat unexpectedly, a couple of John Fowler 16hp, ‘coffee-pot’, single-cylinder ploughing engines of 1875 were acquired in 2013 and, since ploughing engines are the pair’s main interest, it became apparent that the Hornsby restoration would not be tackled for many years to come, if indeed at all.

Mark realised these priorities and since the engine was, to all intents and purposes, to be his at some time in the future anyway, he decided to take on the restoration. In consequence, in June 2015, the Hornsby was loaded on to the low-loader and taken to Mark’s workshop at Ballarat; the return journey being with Mark’s Foden steam wagon, in order to make room in his workshop for the engine.

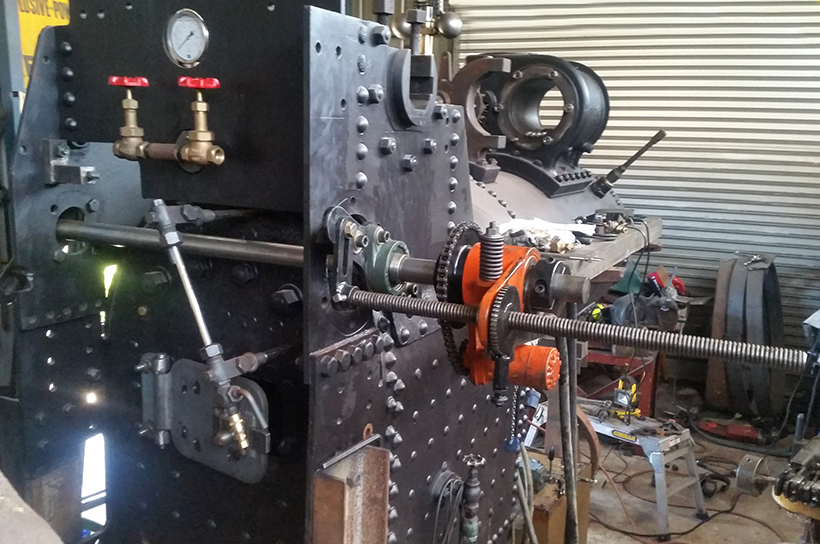

Boiler thinning

An assessment of the Hornsby, from a boiler inspector’s point of view, revealed that there were some thin patches here and there in the boiler, but that the barrel was beyond repair – largely due to excessive, long-term leakage under the cylinder, which had caused severe corrosion. Within days, Mark had arranged for a new boiler barrel to be made, and this was fitted in late July. Everyone got involved in the riveting needed to fit the barrel to the front tubeplate; this being a bigger job than one person can tackle alone! The cylinder was fitted at the same time, at which point Mark was in a position to continue with the overhaul of the engine on his own, as time permitted.

The old and condemned boiler barrel being removed from the throatplate in 2015.

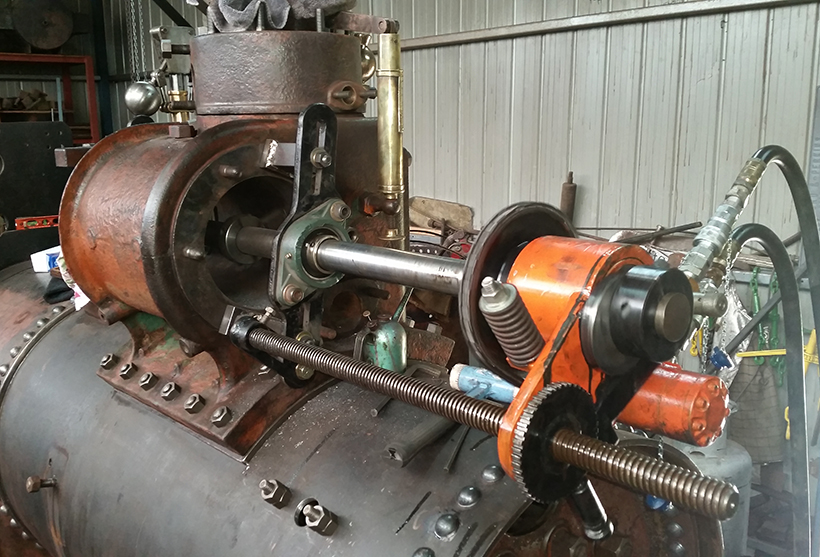

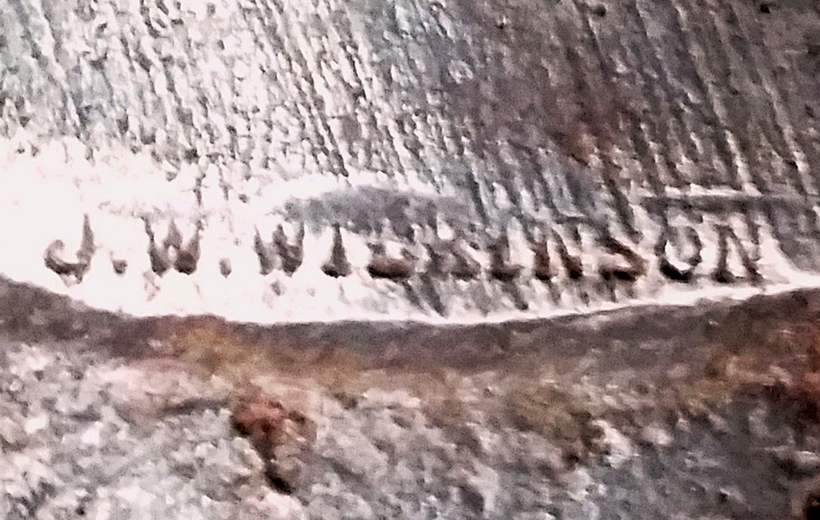

The extensive work required in its rebuild can be gauged from the accompanying photographs. The motion rebuild did reveal one amazing piece of history that, almost certainly, nobody would have noticed previously. When cleaning down and machining the top slide bar, it was found that someone – probably the engine erector, back in 1890 – had stamped his name at each end of the slide bar. With the slide bar detached from the engine, quite visible and stamped with what must have been the smallest letter stamps in existence at the time, was the name ‘JW Wilkinson’. The name was so small that only the closest examination would have revealed it.

The cylinder-boring machine in situ and in operation, during September 2015.

Line-boring the hornplates to ensure an appropriate fit for the second shaft cannon bearing casting, in June 2016.

Drilling rivet holes in the new boiler barrel.

Marked for posterity

One can only imagine that Mr Wilkinson was the engine erector, or some other employee of Richard Hornsby & Co, who left his name on the engine for posterity, even though the chances of it ever being found in later times would have been somewhat remote. Even so, if anyone can throw light on the existence of this man, it would be very much appreciated. Also, if the owners of other Hornsby engines elsewhere have discovered something similar, it would be good to know more details.

A close-up of the name – JW Wilkinson – stamped on the top slide bar.

With Mark’s work pattern, the restoration of the Hornsby engine continued apace. Major work included a brand new, all-riveted tender, and the re-straking of the rear wheels; this latter task one not to be envied. The original rear wheel strakes had been almost totally worn down on the inside, indicating that a lot of road work had been accomplished on the hard-gravel, Tasmanian roads.

One of the engine’s driving wheels in the process of having new strakes riveted on, in July 2016.

The early months of 2017 saw the Hornsby painted as close as possible to its original colour scheme and, by August, it was in steam and being driven on test runs – its new wheel strakes not doing any damage to Australia’s mid-winter, bitumen roads.

So, Hornsby traction engine No 7089 currently lives next to Foden wagon No 7581, and a host of other, equally historic machines. These two occasionally grace the roads during the cooler months of the year, much to the amusement and entertainment of the locals.

Fitting up the crankshaft gears. The rusty one was manufactured during World War 2, during an abortive attempt to put the engine back into service.

The newly-manufactured bull pinion.

The new riveted tender in the process of being offered-up to the hornplates, before being bolted into place.

The Hornsby’s place in Mark’s workshop has now been replaced by the on-going restoration of another Lincoln product – Clayton Wagon’s undertype steam wagon No 1. This also worked in Tasmania, and was the prototype of that later type of steam wagon made in Lincoln, only one production model of which now still exists – at Thursford – No T1136 of 1929. However, the restoration of this ex-Tasmanian prototype example is a story for another time.

To subscribe to Old Glory magazine, simply click here