Saving a wonderful, 1950 Massey-Harris 744D

Posted by Chris Graham on 21st March 2024

Chris Graham meets Stephen Neale to discover all about the eventful life of the 1950 Massey-Harris 744D he rescued 50 years ago.

Stephen Neale’s 1950 Perkins P6-engined Massey-Harris 744D is one of only a few hundred thought to still survive here in the UK, from the many thousands originally built at the factories in Manchester and Kilmarnock.

It’s not often that I get the chance to drive a 74-year-old vehicle these days, but that’s exactly what happened a few weeks ago when Stephen Neale kindly offered me a go behind the wheel of his beautiful, 1950 Massey-Harris 744D. As you’ll see as this story unfolds, it’s a tractor that’s led a very full life but, to look at it now, the uninitiated could certainly be forgiven for failing to appreciate its eventful past.

Stephen grew up on a tenant farm in Gloucestershire, where his father kept pigs and chickens. “I remember dad buying me a Lesney model of a Massey-Harris tractor as soon as he thought I was old enough to play with it,” he recalled, “and I know he was very interested in tractors generally, even though we didn’t have the need of one on our farm. In those days, all the carting around and re-locating of hen houses was accomplished using a succession of old cars!”

Moving on

“Unfortunately, we lost the farm when I was 15, following dad’s death and, as tenants, we had no security and the landlord simply decided to let the farm go to somebody else. I left school at 18 and, without having a clear idea about what to do, made an appointment at what was then the Labour Exchange. I explained that I had an interest in agriculture and was offered a job on a poultry farm near Gloucester.”

The day Stephen bought the 744D, way back in 1974. Note the badly damaged radiator cowl.

Having taken the job, Stephen soon discovered that – coincidentally – he was working for the same poultry breeder that his father had used for many years, as the provider of his day-old chicks. After a while working with chickens, Stephen switched to a job with a pig breeding company, then moved onto a dairy and arable farm before enrolling on a three-year, full-time general agriculture course at the Berkshire College.

“The second year of the course was spent on work experience,” he explained, “and it was while I was on a farm in Wantage that I decided it was time to buy my first tractor. Despite having already driven many types for my previous jobs, my heart was set on a Massey-Harris. Of course, this was back in the 1970s and there was no internet to help with the search; in those days, finding things to buy involved a laborious process of telephoning and chasing leads.”

Then, after about three months of fruitless searching, Stephen was told about a man in Duns Tew – a village near Banbury – who reportedly had a Massey-Harris for sale.

The tractor was fitted with a canvas-clad Lambourne cab and a number of parts from a Fordson E27N Major, including the rear linkage, when Stephen bought it.

It’s the one!

“I wasted little time in getting in touch with the seller, a farmer called Mr Routledge, and arranging an appointment to view the machine. As it turned out, it was a 1950 Massey-Harris 744D and, from the moment I first saw it, I just knew that it was the one I wanted,” he said. “The story was that Mr Routledge had bought the tractor as a fire-damaged machine in the late 1960s. What’s more, as well as most of the rubber, Bakelite parts and wiring having been destroyed by the fire, the engine block had been badly cracked by frost.”

Evidently, Mr Routledge and his son had worked hard to bring the tractor back to life, repairing the cracked block with a screw-on metal plate and fitting replacement components and wiring as needed. But, in typical ‘make do and mend’ style, the farmer hadn’t been terribly concerned about the origin of the parts he used, or the originality of the tractor. It was simply a case of doing the bare minimum needed to get the machine back into working order so that it could begin paying its way.

“The model’s famous Velvet Ride, damper-controlled driver’s seat had been ditched and replaced with a much more rudimentary example from a Fordson E27N. A ‘new’ steering wheel was fitted from the same source, and the farmer had also altered the gear-lever, bending the shaft so that it sat more conveniently between the driver’s knees, rather than off to one side. This change was only possible as the mounting bar for the original driver’s seat had been removed.”

A Fordson E27N seat replaced the original (and more comfortable) Velvet Ride set up, after that seat’s hydraulic damper had been damaged in a fire.

It was also clear to Stephen that the tractor, at some point in its life, had been involved in a fairly severe front-end collision. “Several of the radiator cowl ribs were broken when it arrived with me,” he said, “and the front axle mounting assembly had been welded back together. There was also a non-standard radiator fitted, which, judging by the way the bonnet and front cowl had been ‘adjusted’, was much larger than the original!”

Striking a deal

However, none of the above dampened young Stephen’s enthusiasm for the tractor, especially as it became clear that it was still a runner. “From the moment I saw it in March 1974, I had the feeling that it was a tractor that deserved to be saved. A battery was brought out to the barn in a wheelbarrow, connected and then used to start the engine, which seemed to run well. In those early days I didn’t have any specific knowledge about the model but, once I’d seen it move around a bit I was keen to buy, despite its outwardly scruffy appearance.

“Mr Routledge was asking £250 for the tractor, but I told him that I could only afford £200 (which genuinely was the case!). After a bit of haggling, he suggested £210 including delivery to me in Wantage, and I was happy with that, so the deal was done. Although that sounds very cheap by today’s standards, it was a considerable amount of money then; I was probably earning no more than £20 a week in those days!”

The removal of the Velvet Ride seat’s support member provided the clearance needed to allow the gearlever’s shaft to re-shaped for more convenient use.

Stephen continued: “Of course, in my enthusiasm to buy a tractor, I’d given no thought about where I’d keep it, or how I’d even get it home, so the offer of delivery was a useful start. Fortunately, I was working on a farm by then where there was space, so I could keep it there without a problem.

“The tractor duly arrived on the appointed day but, before he left for home, Mr Routledge reached into his pocket and pulled out the dirtiest pound note that I’d ever seen and handed it to me ‘for luck’. ‘Luck money’ was still a common thing in the mid-1970s, especially on farms and at livestock markets, with sellers giving the buyer a little extra ‘for luck’, in the hope that that would ensure their continued business in the future.”

Time at a premium

Although Stephen was delighted to have bought his first tractor, he didn’t have much spare time to work on it straight away. “Over the first few months I simply concentrated on the maintenance basics, and the only major job I had time to tackle was removing the cab,” he explained. “It was fitted with an old, canvas-sided Lambourne unit which, as well as looking pretty ugly, had no doors. This made getting in and out quite awkward as you had to clamber up and down from the rear.

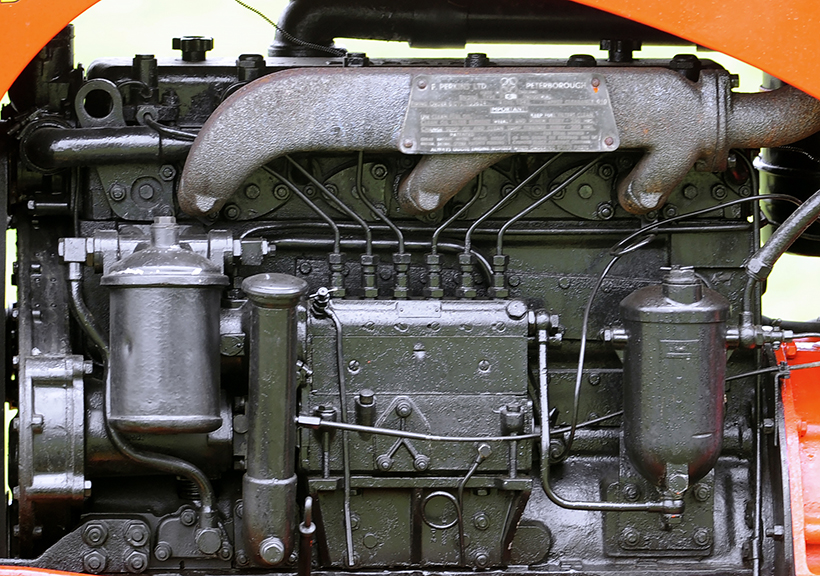

The Massey-Harris 744D’s 4.7-litre, six-cylinder, 42hp Perkins P6 diesel engine is a superb powerplant. This one has required no restoration work, despite the frost-damaged and then patched block.

“I also replaced one of the tyres. Amazingly, the offside rear had a large hole in it that had been ‘repaired’ in true ‘make do and mend’ fashion. A car footwell mat had been sandwiched between the inside of the tyre and the inflated inner tube, and that was evidently thought good enough to keep the tractor operational! Beyond this, though, not much else happened, and the tractor simply sat in a shed for quite a while.”

Two years later Stephen moved to a farm on a big estate near Cambridge, and the Massey Harris went with him. “I was lucky there,” he told me, “because everyone was enthusiastic about tractors, and there was an enormous workshop that I was allowed to use whenever I had any spare time.”

Another work move followed in the mid-1980s, when Stephen became the manager at a farm in Nether Winchenden, near Aylesbury. The Massey-Harris moved again and, at long last, he was able to start thinking seriously about its restoration. “One of the first tasks I set myself was to find a new belt pulley as, for whatever reason, my tractor didn’t have one. The Massey-Harris spare parts situation wasn’t great in those days, and essentially involved dealing in scrap. I also needed to get the over-sized radiator replaced with a proper one and, in 1989, was put in touch with Jim Bracey, from Lambourne, who was an established Massey-Harris enthusiast and potentially a good source of spare parts.”

Like most of the rest of this tractor, the dials are all original, providing information on (left to right) oil pressure, amps and engine temperature.

Unexpected acquisition

The good news was that Jim had a belt pulley and was prepared to sell it for £25 although, as things turned out, it wasn’t quite as simple as that. “Jim told me that I could have the pulley for that price if I removed it from the tractor myself,” Stephen recalled. “So I agreed to that but, when I arrived at the farm, there wasn’t a soul to be seen. I eventually found somebody, but was told that Jim was out. However, I was pointed in the direction of the tractor and invited go and retrieve the part I needed.

“I’d taken some tools and was initially amazed at how easy it was to undo the four bolts securing the pulley. Unfortunately, I then realised that the pulley itself had been welded to its shaft, and this meant that there wasn’t enough clearance to get it off without first removing the rear wheel (it sits partially behind the tyre).

“After struggling with this for a while – the tractor was half buried in undergrowth – I’d all but given up when Jim and a friend appeared and began helping. But, even with a 10-foot scaffold pole as a lever, the three of us couldn’t make any headway, so Jim started thinking. “OK”, he eventually said, “if you give me five times the price we agreed for the pulley, then you can have it, with the tractor attached!”

Stephen went to buy a replacement belt pulley for the 744D, and came home with this! It’s a 1952, long-frame Massey-Harris 744D that was converted for use as a ‘tandem’ tractor, hence the lack of front wheels, seat and steering wheel.

“But when I looked more closely I could see that the tractor was no ordinary machine. It had no front wheels or axle, no seat or steering wheel, a girder framework across the top of the engine, no bonnet and an odd-looking set of controls ahead of the exposed radiator. It was a fascinating looking device, so we agreed a deal and I trailered the pulley – with tractor attached – back to our farm.

“What I’d actually bought had originally been a 1952, long-frame Massey-Harris 744D that Jim Bracey had converted to run as a ‘tandem’ tractor. He’d wanted a Doe but, without the money to buy one at the time, decided to build his own Massey-Harris equivalent. Interestingly, Jim’s 744D, despite being a later model, was fitted with the 28in rear wheels normally found on the very early models.”

Real progress

Now Stephen felt like he was starting to make some real progress, and he’d also decided that he would restore both machines and re-create Jim Bracey’s dual tractor combination. “The first job was the transfer of the belt pulley, after which I took the three-point linkage off the ‘slave’ machine and fitted that to my original 744D, which had arrived with me equipped with a very tatty Fordson E27N Major set-up.

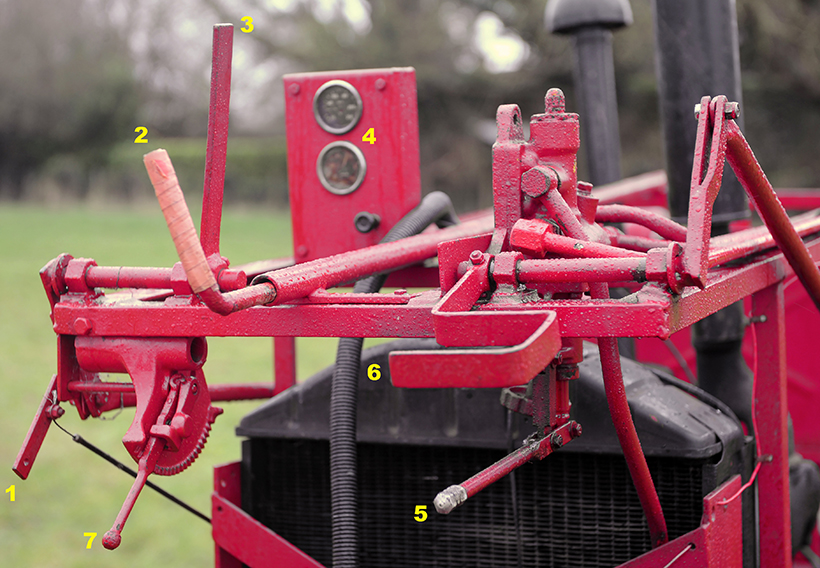

It took some time for Stephen to work out and then fabricate the controls for the tandem tractor. They are as follows: 1. Cable-operated throttle butterfly (pneumatic governor) control, 2. Gear selector (left and right are reversed in operation), 3. Rear linkage (lift arms), 4. Temperature gauge (top) and oil pressure gauge. The black knob is ‘pull to stop’, 5. External service connection – lift for pressure, lower to return, 6. Clutch, with lever in engaged position – it’s lifted to disengage, 7. Throttle lever, currently set in idle position, push to increase revs.

“Unfortunately, the ‘tandem’s’ engine was seized solid, although that wasn’t such a disaster because I knew it was the wrong unit – it was a lorry engine – so I wasn’t too concerned about scrapping it. My search for a replacement Perkins P6 engine brought me into contact with a farmer based near Oxford, Mr Watson, who had a P6 that he wanted to sell; it had been running his grain dryer. He’d bought a tractor with a wrecked gearbox, unbolted the back end and connected the cradled engine, via the clutch output shaft, to a big fan. He sold that to me and then I had all the bits to complete the restorations of both the 744D and dual tractor, which I christened ‘Bracey’, in honour of the man who built it.

“I repaired the 744D’s damaged front grille by fabricating new strips that I cut from a suitably curved panel taken from an old John Deere combine harvester, and welding them into place. The rest of the tractor’s tinwork is predominantly original, although some repairs to the cowling and along the bottoms of the mud guards (near the footplates) were necessary.”

Mechanical matters

“Very little mechanical work was required during the restoration, as I’m a great believer in the old adage: if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it! I’m quite fastidious about routine maintenance so regularly change oil and filters but, overall, if something’s working reliably then, generally, I opt to leave it well alone. Granted, the transmission is quite noisy in the low gears, but I don’t really have a problem with that as I’m not using those for any length of time. I really don’t see the point of investing both the time and money needed to make all aspects absolutely perfect on a machine that, typically, only runs for about 60 hours a year.”

Bracey, the dual tractor which, appropriately enough, Stephen restored in tandem with his standard 744D. Operating the pair takes some getting used to, as you might imagine.

Talking of running, Stephen says that he has no real idea about what sort of a working life his tractor led. “I can imagine that it got used quite hard by Mr Routledge, and that its maintenance left a little to be desired during that period. When I bought it in 1974, the oil filter had ‘1970’ scratched on it, so that was certainly well overdue a change!

“The tractor was finished in 1990 and I completed Bracey the following year. It took quite a while to work out the control mechanisms for the tandem tractor, because there wasn’t much of the original set-up left. The two machines are completely independent, and the rear one pivots on the towing hitch and is unsteered, simply following as a trailer would. Nothing is synchronised in between the two engines, so the throttle, clutch and gearbox are all set using hand-operated levers working through a series of linkages.

“Fortunately, being diesel engines, the two motors are fairly flexible, so keeping them balanced isn’t too much of a struggle, although controlling the rear machine by turning around in the driving seat does take a bit of getting used to. It’s a bit frightening to start with and, although I’ve offered plenty of people the change to drive it over the years, very few have been keen to have a go!”

Stephen Neale beside the beautifully repaired radiator cowl of his Massey-Harris 744D.

Ceremonial duties

Two years ago the Massey-Harris was a requested guest at Stephen’s daughter’s wedding. “Rebecca grew up with tractors,” he told me, “and so was very keen to have the 744D at her big occasion. By then, though, it had been 32 years since I’d finished the restoration and, although Rebecca was very happy with the look of the tractor, I really couldn’t have her climbing onto a dirty machine in her white wedding dress. So I set about making the tractor presentable, and began by tackling the ingrained dirt with a steam cleaner. Unfortunately, as well as removing the dirt, this blasted off quite a lot of the paint too, which meant that I had to resort to Plan B – a complete respray.

“I tackled that job myself, as I’d done 30 years ago, this time getting the paint from the very helpful Vintage Tractor Spares, in Lutterworth (vintagetractorspares.co.uk). I opted for traditional, cellulose-type paint, which I sprayed myself, mostly outside in the garden at home. For my first restoration I had to guess at the shade of red, and lots of people said it was too dark. I also mixed the yellow for the wheels myself and people criticised that, too. I was told frequently that the wheels should have been finished in a cream colour, but I think that was wrong. I reckon that lots of people were simply remembering old, faded yellow paint that they’d seen on Massey-Harris tractors back in the day, which had turned a cream colour.”

Today Stephen’s 744D is mainly restricted to appearances on local road runs and at the occasional show. He still undertakes a bit of agricultural contracting work, but has other, newer tractors that get used for that. The Massey-Harris enjoys a more sedate lifestyle these days; the kind of well-cared-for retirement that befits a tractor that’s been through so much. And yet, despite the relative rarity of the model and its increasing desirability among collectors, Stephen remains very matter of fact about its continued use.

On the run! I first spotted Stephen and his 744D on last year’s Chiltern Tractor Road Run; a popular event that he’ll be involved with again this year (May 19th, combined with the Fawley Hill Steam & Vintage Transport Festival).

“I got the distinct feeling when I first came across this tractor, 50 years ago, that it was a machine that deserved to be saved, and I’m really glad that I made the effort to do so,” he explained. “Nevertheless, I’m certainly not too precious about it and if it takes the odd knock here and there, or the paint gets chipped, I realise that that’s not the end of the world.

“I’m a great believer in the view that tractors always were – and remain – utility vehicles designed to work and, as such, I think it’s right and proper that, even when restored, they should continue to be operated as their designers intended. I’m convinced that most of the pleasure from owning a classic tractor should come from getting out and using it, not locking it in a garage somewhere out of sight and wrapped in cotton wool. Consequently, I’m always looking for an excuse to get out and about on my machines.”

This feature comes from the latest issue of Classic Massey & Ferguson Enthusiast, and youy can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

1907 Stanley steam car keeps getting better

Next Post

Sprat & Winkle Run highlights in sunny Hastings!