Medical support at sea

Posted by Chris Graham on 30th January 2020

Medical support at sea is part of a warship’s operational function, but when deployed in hostile maritime battle space, a naval force requires capability on a larger scale that can deliver emergency care, surgical expertise and care for mass causalities.

The Falklands (1982) and Gulf (1990) wars proved the value medical support at sea – hospital ships that were adopted vessels taken up from commercial trade. The challenge for the Royal Navy is that such vessels are expensive, big-ticket items and, in today’s fiscally-challenged economy, defence chiefs rarely regard such specialist ships as a ‘must-have’, until conflict erupts, of course. Then, in the case of the Royal Navy, a commercial vessel is often taken up from trade, and converted for the role. However, in the past three years there has been growing pressure in the UK for the Department of International Development to fund a dedicated capability.

The RFA Argus pictured in the Persian Gulf, during Operation Granby, when she first deployed as Primary Casualty Receiving Ship (PCRS). (Photo: David Reynolds/DPL)

The move comes as the merchant ship, RFA Argus, which currently provides a unique form of hospital support and has been in service since 1982, is due to be retired during the coming decade, despite a recent major overhaul. This event will leave the military with no naval resource that can support deployed British military forces.

The Gulf War (Operation Granby) highlighted a series of military concerns facing British forces, including the threat of a chemical attack, which could cause a serious, logistical challenge with regard to evacuating and treating injured personnel.

During those conflicts, the Royal Navy had no official hospital ship, and there was concern about the justification of procuring or assigning a dedicated vessel to the role of ‘hospital ship’, which may only see limited operational use.

Commander Paxton Dewar, a Royal Navy medical officer, proposed installing a medical complex within a naval support ship, which could be used to treat and evacuate casualties, and wouldn’t need to be officially listed as a hospital ship. His concept was called the Primary Casualty Receiving Ship (PCRS), and was first deployed in Operation Granby. It gave the Navy a capability, but also allowed the ship to retain its operational role.

The hospital complex aboard RFA Argus is complex, and includes a surgical capability. (Photo: Noel Harrison/DPL)

His vision saw a surgical capability and hospital wards being installed inside the RFA Argus, which was deployed into the Persian Gulf in support of the UK forces on land and at sea. Argus – formerly the MV Contender Bazant – had been taken up from trade by the Ministry of Defence in 1982, to support the Falklands war, and was then purchased and commissioned into service as a naval support ship in 1984. It had a specific role as an Aviation Training Ship, for Sea King helicopter pilots.

Medics aboard RFA Argus take part in a medical evacuation exercise to hone their skills. (Photo: Chris Smith/DPL)

International rules on the declaration of a vessel as a ‘hospital ship’ are governed by the Geneva Convention, which states that dedicated hospital ships must be painted white and clearly highlighted as a medical facility. But, while the UK needed the capability, there was a reluctance to dedicate such a large asset to a permanent medical role. So Commander Dewar’s concept of a PCRS provided an opportunity for the deployed hospital, while still allowing the ship to remain grey and not having to display red crosses.

The hospital aboard RFA Argus has expanded since it was first deployed, and includes a fully-equipped, 100-bed medical complex, an emergency department, resuscitation and surgical facilities and a radiology suite complete with a CT scanner (if necessary, all this can be unbolted and removed). Since commissioning in 1990, the Argus hospital has received wide acclaim, and deployed on operations in the Adriatic in support of the UK’s contribution to the United Nations operation, then in support of the mission in Sierra Leone. It was also successfully used in 2003, off southern Iraq, where Argus was deployed in support of amphibious operations off the Al Faw Peninsula.

Sea King helicopters on the deck of the RFA Argus during her deployment to Croatia in the Balkans on United Nations mission. (Photo: David Reynolds/DPL)

The importance of a ship such as Argus was highlighted when the vessel was deployed for six months in 2015, supporting the UK response to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, known as Operation Gritlock. The ship’s capability was instrumental in providing support to the personnel on the ground, using boats and Merlin helicopters to transport personnel and materials to all areas of Sierra Leone. She effectively acted as a logistics hub to support the work ashore, and did not embark any ebola patients to her 100-bed medical facility.

Hospital ship background

During the 17th century, the concept of a hospital ship evolved to support sick and wounded sailors. Their role was to deliver essential treatment and transit sailors to the hospitals ashore. The earliest record of a hospital ship is the Goodwill in 1608, and it’s belived she served in the Mediterranean.

Throughout the reigns of Charles II and James II, two ships were kept for this role, and deployed when war broke out with France in 1689. From 1742 until 1828, stationary hospital and convalescent ships were moored in the main naval divisional ports of Chatham, Plymouth and Portsmouth. During the Crimean War, hospital ships were used to evacuate injured soldiers from the Siege of Sevastopol in a fleet of converted vessels.

In 1907, Hague convention protected hospital ships, and gave them immunity from attack providing they bore prescribed distinguishing marks – that being a large red cross. During the First World War, the RMS Mauretania and the Aquitania were among many ships converted for service as hospital ships and, by the end of the war, the fleet had more than 70 in service. The capability expanded in the Second World War although, despite their status, five hospital ships were sunk by the Germans.

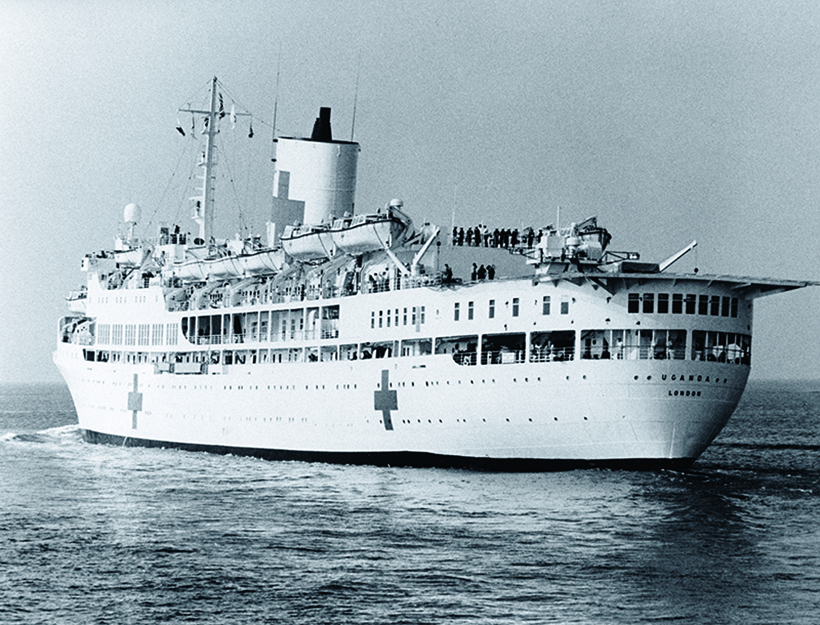

The SS Uganda a commercial ship taken up from trade and converted for use as a hospital ship in the 1982 Falklands war. (Photo: Peter Holdgate/DPL)

In the post-war years, there was no obvious or operational demand for hospital ships. UK operations in Malaya, Aden and Cyprus were supported by land-based medical teams but, in 1982, commanders quickly identified that the pending conflict in the south South Atlantic would require the support of hospital ships. The Navy requisitioned the P&O cruise ship Uganda to be converted for use as a hospital ship, alongside the survey ships HMS Hydra, Hecla and Herald.

The Royal Yacht, which was constructed so that it could be converted into a hospital ship, was not deployed. Uganda sailed for the Atlantic from Gibraltar, with 136 medical staff, and her call sign was ‘Mother Hen’. The first casualties the ship received were from HMS Sheffield. By the end of the campaign, the ship’s crew had treated 730 casualties, 150 of whom were Argentine prisoners.

The future

The US Navy has, for many years, deployed a dedicated hospital ship. But, at a time when the Royal Navy is facing manpower shortages, a dedicated vessel may be seen as yet another challenge given that personnel are needed for the carriers and the frontline fleet. A ship funded and managed by DFID, would still need to be maintained and managed when not deployed, and would still need a military contingent aboard if deployed in support of UK operations.

The US hospital ship Comfort; a converted commercial ship, which has extensive facilities. (Photo: Bill Masha/DPL)

The fleet’s favoured concept remains that of the PCRS. A hybrid vessel that’s able to deliver care while, at the same time, utlising its capability in support of the wider fleet. This presents a more flexible option. When not deployed in its PCRS role, Argus has supported amphibious operations, assisted in humanitarian missions and provided a tier-one medical resource on operations off West Africa.

Of course, the big challenge for DFID, or the Ministry of Defence, in funding a dedicated ship will be how best to utilise it when it’s not on operations, while maintaining the policy of the Geneva Convention that the vessel is only used in a medical role.

When she was in office at DFID, Penny Mordaunt indicated that she fully supported the concept of her then department exploring the cost of a specialist ship. But, at a time when the National Health Service is seeking uplift in its budget, and defence is calling for more investment, it’s unlikely that a decision to spend more than £300 million on a new hospital ship will be politically acceptable.

While large American aircraft carriers are all fitted with major surgical facilities, the United States still opts to maintain hospital ships. The capability is also maintained by Russia, which lists three vessels dedicated to the role, Peru that has converted a former passenger ship, Indonesia, which has adapted a former landing ship and Brazil, which has four hospital vessels. China operates two hospital ships in support of the People’s Liberation Army and Navy (PLAN). In addition, Spain operates Mercy ships while India lists one vessel, although it’s not clear if this ship is still operational.

Argus pictured on deployment in the Gulf where she can support Royal Marine operations, deploy naval helicopters and provide the PCRS role. (Photo: Pete Holdgate/DPL)

The United States Navy operates two hospital ships – the USNS Mercy and USNS Comfort. Both are converted San Clemente-class tankers, displacing approximately 70,000 tonnes, and have a 1,000-bed capacity and 12 operating theatres. They’re also equipped for the widest range of medical treatment options. Mercy is home-based on the Pacific coast and Comfort, the Atlantic. Both are activated in response to need, rather than being permanently in operation.

To subscribe to World of Warships, click here