Sink the Bismarck!

Posted by Chris Graham on 13th March 2020

Prime Minister Winston Churchill provided the battle cry when he commanded the Royal Navy to ‘Sink the Bismarck’, as Paul Baker recounts

‘Sink the Bismarck’ was Churchill’s command. He wanted this hugely-powerful battleship to be destroyed, and didn’t care how it was done.

May 1941 saw one of the defining moments in the history of the Second World War, when the Royal Navy were pitted against the might of the German fleet; the hugely powerful battleship Bismarck.

German naval doctrine throughout the Second World War was to attack the United Kingdom’s maritime lifeline; its merchant fleet bringing food and supplies into the country. Up until mid-1941, the plan worked beautifully, bringing Great Britain perilously close to its knees.

In the spring of 1941, however, Adolf Hitler demanded the Kreigsmarine display its mastery of the North Atlantic, and ordered Grand Admiral Erich Raeder to devise an operation that would decimate the British merchant marine. Raeader’s answer was to use the battleship Bismarck.

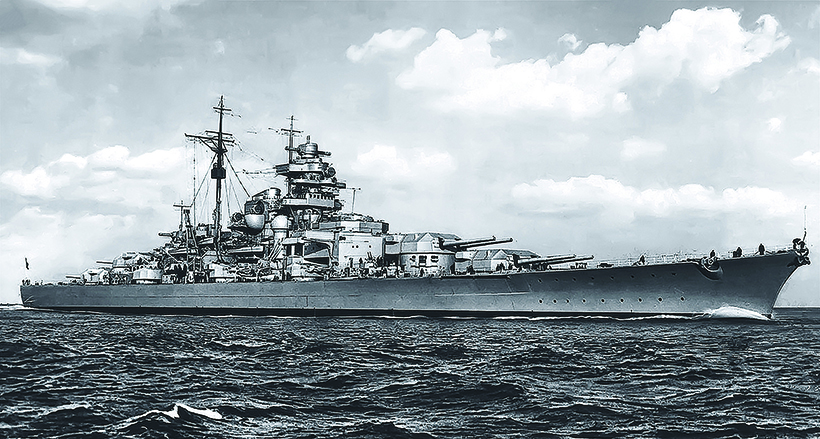

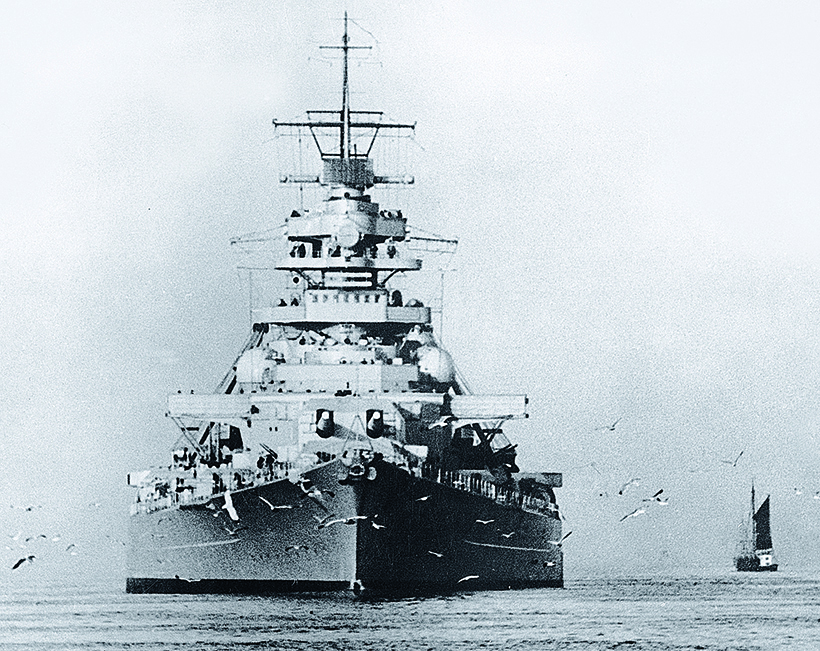

Bismarck was a most impressive warship. Designed in secret and constructed by the Hamburg shipyard of Blohm and Voss, the battleship far exceeded its treaty limitations of 35,000 tons – by almost 15,000 tons – and measured almost a sixth of a mile long. Her main armament of eight 15in guns could fire shells weighing the same as a family car to a range of more than 20 miles. Her armour protection was also extraordinarily good, with thick armour plating protecting all the ship’s vital areas.

The Bismarck’s designers were so confident in the warship’s ability to inflict and take punishment, that they claimed she was unsinkable. There was, however, just one area that proved to be her undoing. Her Achilles heel was that she had only a single rudder. From the time of her launching, by Adolf Hitler, on February 14th, 1939, to her destruction at the hands of the Royal Navy, the Bismarck’s wartime career lasted for just over two years.

Bismarck sails

Bismarck’s first and final mission had been planned to include the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen and the battlecruiser Gneisenau. The latter, however, had been attacked at the French port of Brest, on April 4th, 1941, by a force of 90 Royal Air Force aircraft, although no direct hits were achieved. Fearing her vulnerability, the Germans moved her from the No. 8 dock and into the anchorage. This presented a wonderful target for another air strike, and a plan using six Bristol Beauforts from 22 Squadron based at St Eval in Cornwall, was hatched. Half of the force carried bombs, the other half torpedoes.

But only one of the slow-flying and old aircraft – piloted by Flying Officer Ken Campbell – made it to the target and attacked the Gneisenau with his torpedo. However, the strike was a good one and the German battlecruiser was severely damaged, which removed her from the planned North Atlantic sortie with Bismarck. Sadly, Campbell’s Beaufort was shot down with the loss of all her crew, and Flying Officer Campbell was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

Nevertheless, preparations for Operation Rheinubung (Rhine) continued and, on May 18th, 1941, Bismarck took passage from Gdynia in company with the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen. Intelligence reports from Sweden and later, Norway, confirmed that the battleship was making her way through the Kattegat and into the North Sea.

Naval reaction

At Scapa Flow, Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleet, Admiral Sir John Tovey, assessed the situation from his flagship, the battleship King George V. Immediately, two cruisers – HMS Suffolk and HMS Norfolk – were ordered to patrol the Denmark Straits between Iceland and Greenland, while a second pair of cruisers were to patrol the waters between Iceland and the Faeroes. Bismarck would have to break into the North Atlantic using either of these two routes as, using the narrow English Channel, would have been extremely dangerous and foolhardy.

But, Admiral Tovey’s task was made worse by a lack of information about the German battleship’s exact location. Numerous reconnaissance flights by RAF aircraft had failed to find her, but then came success when two Photographic Reconnaissance Unit Spitfires from Wick, flew to search the Norwegian coastline. Spitfire PR.IC X4496, flown by pilot officer M Suckling, discovered Prinz Eugen first, and then Bismarck lurking in two fjords near Bergen. The Bismarck was moored in Grimstad fjord.

Once the film had been processed, the images were studied and an attack plan was hurriedly formulated. Eighteen elderly Beaufort bombers armed with 250lb bombs flew from Wick, but bad weather forced them to return without making an attack. At roughly the same time, the 25-year-old battlecruiser and pride of the Royal Navy, HMS Hood (flagship of Vice Admiral Holland), and the new battleship, HMS Prince of Wales, plus escorts sailed from Scapa Flow, making for a position south of Iceland. From there it was hoped that the force could sail to intercept the German ships. The new aircraft carrier, Victorious, the battleship HMS Rodney and the battlecruiser Repulse, were also detached to Admiral Tovey’s force.

As dawn broke on May 22nd, 1941, another reconnaissance mission was organised, but this time involving a Martin Maryland AR720 from 771 Squadron, flying from the Naval Air Station at Hatson, on the Orkneys. At the controls was Lieutenant N Goddard, along with the stations executive officer, Commander R Rotherham. Both men had volunteered to search around the fjords of Bergen, and the mission proved beyond doubt that the two warships had left their anchorages.

Hood explodes

With Bismarck and Prinz Eugen on the loose, no expense was spared in trying to track them down. RAF Coastal Command organised sorties from Iceland, with Lockheed Hudsons and Fairey Battles. In addition, Consolidated Catalinas were flown from bases in Scotland. The sorties turned out to be fruitless, with the task being made much harder by the extremely poor weather conditions in the area.

Eventually, the Royal Navy discovered the German ships when the cruiser Suffolk spotted the unmistakable and sinister shape of the Bismarck, at 19:22 on May 23rd. A little later her sister ship, Norfolk, discovered her nemesis was only six miles away. The Bismarck fired the first shots of the battle, but Norfolk made smoke and managed to slip away to a safe distance.

A Short Sunderland aircraft from 201 Squadron in Reykjavik, Iceland, was ordered on to a patrol over the Denmark Straits. The Sunderland’s timely information on the course and speed of Bismarck and Prinz Eugen, proved invaluable to the gathering Royal Navy armada. An uneasy night was spent aboard both German and British ships and, as dawn broke, everyone knew that battle would be joined that day.

At 05.52am on May 24th, the battle started in earnest. The German pair concentrated their fire on the battlecruiser Hood. Moments later, a shell penetrated the relatively thin armour of the battlecruiser and detonated in a magazine. The resulting explosion split the pride of the Royal Navy in two, and took all but three of 1,419 sailors to their watery resting places. Above the battle, a Lockheed Hudson of 269 Squadron was ordered by the cruiser HMS Norfolk, to investigate whether hits had been secured against the German battleship. The reply was: “Enemy course 220 True. 30 knots. No fire, but Bismarck losing fuel.”

A terrible loss

Hood’s destruction was felt like a knife wound in the heart of the Royal Navy. It also robbed the force of some of the fleet’s most powerful guns. The Royal Navy poured every available asset into the fight, even robbing other areas of vitally important ships. Prime Minister Winston Churchill, once the First Lord of the Admiralty himself, felt the loss of the Hood personally, and issued his famous call to arms; ‘Sink the Bismarck’. He didn’t care how it was achieved, only that it was done. One of the first moves was to take the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal, the battlecruiser Renown and the cruiser Sheffield, from Force H at Gibraltar, to bolster the Home Fleet’s resources.

Aboard the Bismarck, the crew were buoyed by their unexpected victory against the Hood, but there was concern over the fuel oil that was being lost. This aspect of the battle has sometimes been overlooked. The British had become aware of the oil leak when Hudson aircraft of 269 Squadron and Catalina’s of 240 Squadron had spotted it.

The German Navy’s destruction of the Hood had handed the Kreigsmarine a glorious propaganda opportunity, but it was clear that the Bismarck needed repairs, so the decision to head for Brest was made by Admiral Lutjens and Bismarck’s captain Ernst Linderman, as the French port offered protection from both U-boats and the Luftwaffe.

Swordfish attack

Royal Navy high command reasoned that this was a probable course of action, and hurriedly put together an attack by Swordfish aircraft flying from the aircraft carrier Victorious, on May 24th. Nine aircraft took off while the ship was 100 miles distant, armed with torpedoes. They left the deck at 22:15 followed, 40 minutes later, by three Fairey Fulmars of 800Z Squadron, which were intended to provide a diversion for the main attack.

As the Swordfish dove down for the final moments of their attack, they launched their torpedoes under withering anti-aircraft fire. Only one of the torpedoes found its mark, and had little effect. All the Swordfish returned safely to Victorious, although two of the Fulmars failed to make it back.

Under the cover of darkness on May 24th, Prinz Eugen detached from the battleship and escaped back to Germany, while the Bismarck managed to evade the shadowing British cruisers. It is likely the German capital ship could have escaped had it not been for air power. For frantic hours, the British searched for the mighty battleship, and it wasn’t until 10:30am on May 26th that Bismarck was rediscovered, 700 miles northwest of Brest, by Catalina flying boat AH545 of 209 Coast Command.

The Catalina force stuck to the German ship like glue, continuously updating the British battleships of her every move. They were getting closer to closing the net but, with her superior speed, Bismarck could still escape their clutches. One final throw of the dice was ordered, and Swordfish from HMS Ark Royal were ordered to fly in atrocious weather conditions to attack with torpedoes once again.

The order of battle had changed considerably at this point; Repulse and Prince of Wales had joined Victorious in departing the battle zone, due to lack of fuel. But the powerfully-armed battleship Rodney had joined the group, while King George V was 130 miles away, with Dorsetshire and Force H closing the distance steadily, to just 70 miles.

At 00.50 on May 26th, 14 aircraft took off from the pitching flight deck. However, embarrassment was caused when the aircrew mistook the cruiser Sheffield for the Bismarck, and attacked her with their torpedoes. Thankfully, the Sheffield’s Commanding Officer, Captain C Larcom, skilfully avoided all the torpedoes, which failed to explode, or exploded upon contact with the waves, highlighting a weakness in their magnetic fuses.

The Ark Royal attacks

Frustrated, the aircrews waited, wanting another chance to destroy Bismarck, and they got just one, final opportunity to do so. The aircraft were hurriedly refuelled and rearmed with new contact fuses for fresh torpedoes. Fifteen Swordfish left the deck at 19:10, using Sheffield – positioned 12 miles astern of Bismarck – as a way marker, then flew on to launch their attack on the battleship.

The first of the Swordfish struck just as darkness was descending, at 20:47, and all faced intense anti-aircraft fire from Bismarck’s secondary guns. For half an hour the British aircraft pressed home the attack, with two torpedoes hitting home. One hit amidships caused only superficial damage, but the second hit right aft, jamming the ship’s single rudder in the hard-to-port position. This simple, almost inconsequential hit meant that Bismarck was doomed. She steered around in long circles which allowed the Royal Navy to catch up. It was the beginning of the end as the heavy, big-gunned Royal Navy warships started to pound the Bismarck to destruction once they were within range.

Survivors from the Bismarck being rescued by HMS Dorsetshire.

The end of the Bismark

At dawn on May 27th, the morning light revealed revealed a shattered, burning wreck. The Royal Navy moved in closer and fired salvoes of torpedoes at the Bismarck, at 08:47. More torpedoes were dropped into the sea from a dozen Swordfish aircraft from Ark Royal. Under the weight of this onslaught, the Bismarck sank at 10:36, and only 115 sailors from her crew of over 2,000 were saved from the freezing ocean waters.

Adolf Hitler, always a mercurial character at the best of times, saw the loss of Bismarck as the signal to lose faith in his Navy’s surface units. This was a decision which had a profound effect on the rest of the Battle of the Atlantic for years to come. Hitler placed his belief in the effectiveness of the U-boat fleet, and consigned Bismarck’s sister ship, Tirpitz, to ignominiously languish in Norwegian fjords until, she too, was sunk primarily with the use of air power, in 1944.

You can subscribe to World of Warships by clicking here