Amazing ploughing leviathans

Posted by Chris Graham on 19th July 2020

John and Henry McLaren had a great reputation in the steam era, but recognised the need to change to internal combustion technology. This resulted in some amazing ploughing leviathans, as Bernard Holloway explains.

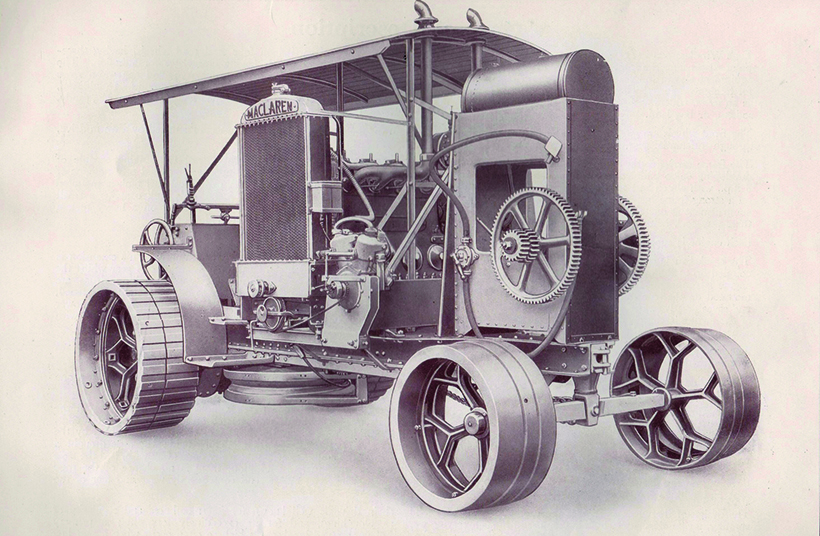

Amazing ploughing leviathans: Note the twin-cylinder donkey engine and the spare gears mounted at the front.

Steam-powered, double-engine, cable ploughing and cultivation is a marvellous sight and, these days, is a great pull at shows and events, conjuring up a nostalgia for those bygone days.

While they are fascinating to watch, these heavy leviathans, with their long-bodied boilers and underslung winding drums (other configurations also available), were in their day and still are, expensive to purchase and run. Consequently, they were mainly operated and owned by agricultural contractors; the constant attention to power plant and equipment keeping a team of men busily employed during the long hours of the working day.

Of course, mechanisation and innovation are the path to increased agricultural yield and profitability by the lowering of production costs, and the plough certainly achieved that in experienced hands. Progress never stands still and, this era was no different. The manufacturers of agricultural machinery researched and developed – much by trial and error – new equipment.

Their mission was to bring this to the market, and the attention of the hard-working Victorian farmer. He was probably entrenched in old methodology, sceptical of any true gains, particularly with one demanding a considerable financial outlay when he was already striving to make ends meet.

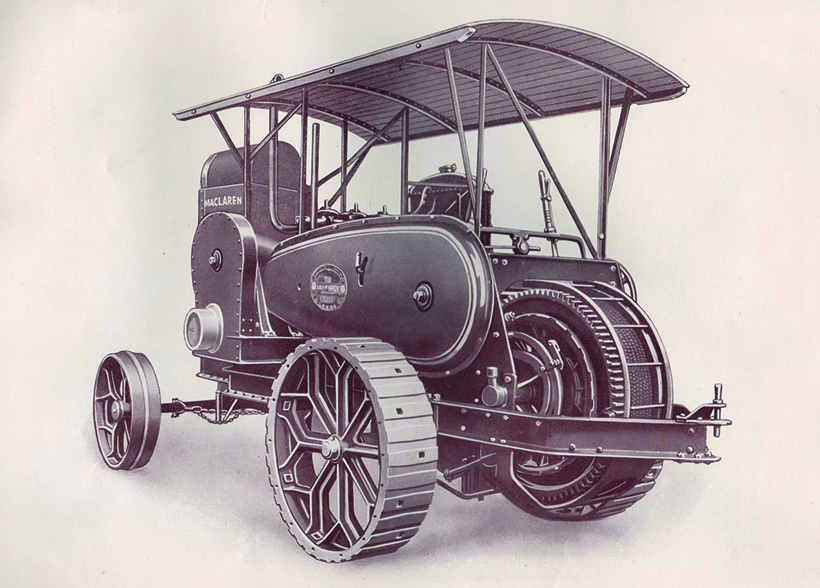

The winding gear is fitted with a locking arrangement, to prevent selection of more than one gear at a time.

Valuable experience

John and Henry McLaren were typical of a new wave of Victorian entrepreneurs who understood the needs of the market, and had the marketing savvy to merchandise them. Serving their apprenticeships with Gateshead colliery locomotive manufacturers, Black Hawthorn, the brothers gained a thorough grounding in steam and locomotive engineering.

After leaving this employer, they trod separate paths; John to Ravensthorpe Engineering, and Henry John to W&J Cardwell. They built upon their knowledge and skills working, respectively, on pumping and stationary engines and, in 1876, the pair went into partnership, establishing an agricultural manufacturing business, the Midland Engine Works in Hunslet, Leeds. The town already had a reputation as a centre for engineering skills and manufacturing steam machinery, because established companies such as John Fowler, Kitson & Co and the Hunslet Engine Co were located there, so the McLarens were in good company.

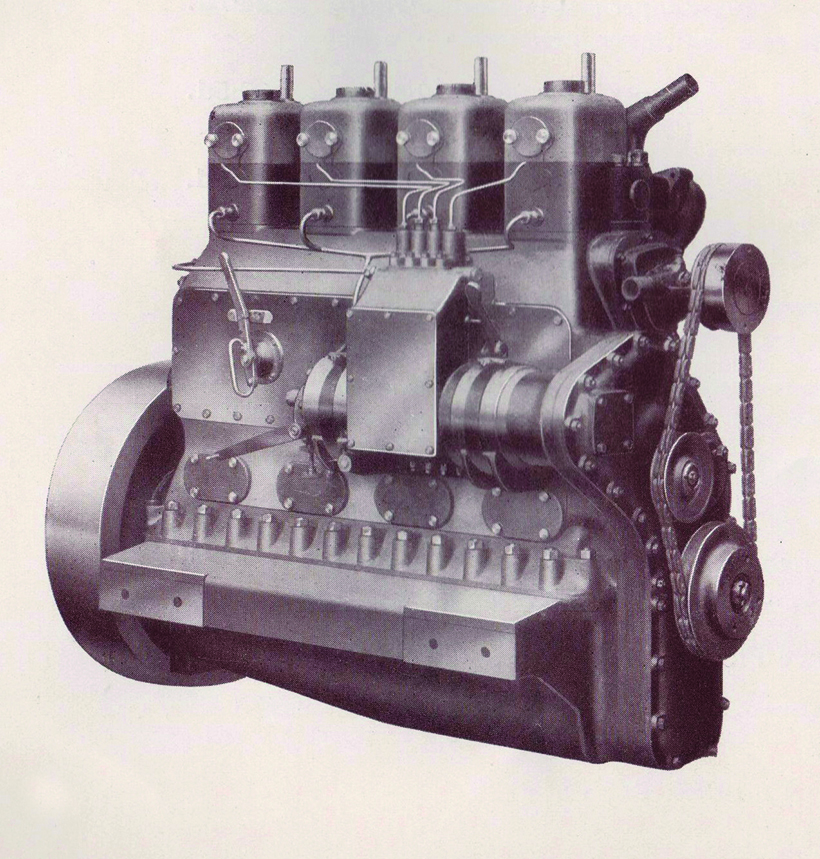

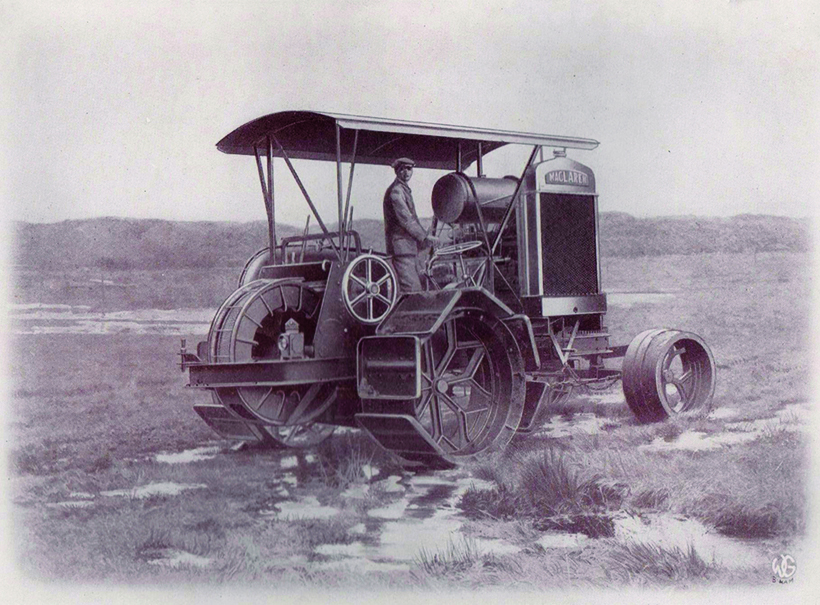

The four-cylinder, front-mounted diesel engine produced 60-70hp, at 800rpm.

Reputation-building

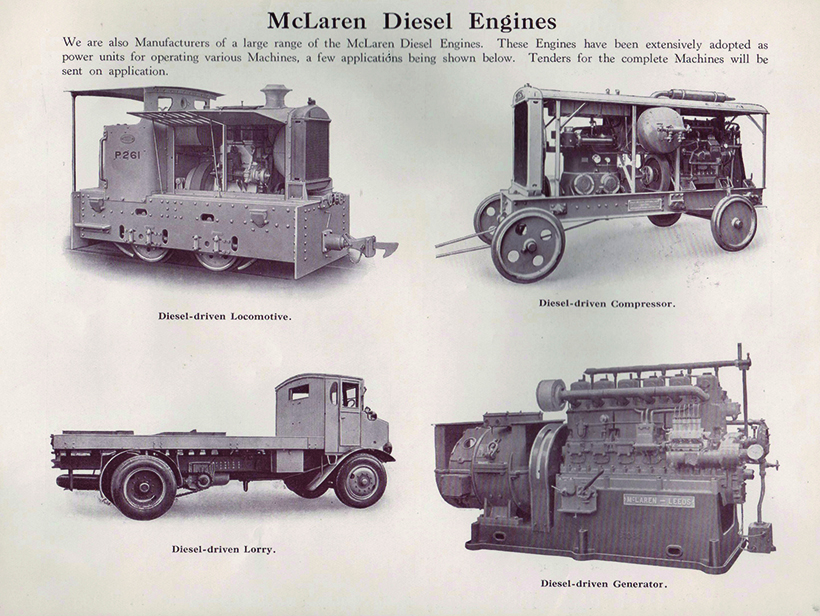

The brothers quickly established a reputation for manufacturing a variety of solid, reliable and mainly steam-powered machinery, traction engines, (and later locomotives), rollers, pumping machines, stationary engines, as well as agricultural equipment including cable tackle for use with the double-engine system.

In the early days of the business, McLaren steam engines powered the company’s machinery but, like the horse, steam was an ageing technology, and destined to be superseded by the internal combustion engine, powered by either petrol, paraffin or alcohol and, much later, diesel.

During the early decade of the 20th century, even the well-regarded but heavy steam ploughing engines weren’t immune from progress. It was recognised that something lighter, easier to manoeuvre across fields and on the highway, and less labour-intensive was required. But, the First World War intervened, and any meaningful development at McLaren’s was concentrated on the war effort during that time.

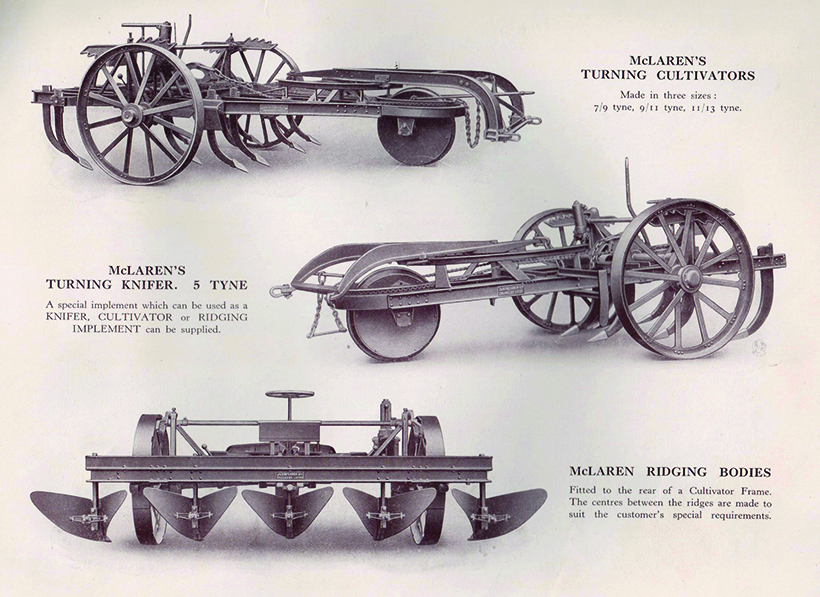

‘No set of cable tackle is complete without the McLaren Turning Cultivator,’ claimed the brochure, ‘for breaking up the hard, sun-baked land in the dry season, we could not suggest a better implement.’

The Windlass

After the horrors of WW1 ended, the company developed a new piece of equipment and, in 1920, produced a Dorman engine-powered, cable-ploughing windlass. The aim was to supersede the expensive, heavy, soil-compacting steam engine.

The new machine offered more versatility, was lighter and of simpler construction. It was also cheaper to produce and purchase. Under a later agreement, in 1926, with Benz, McLaren fitted its engines to the windlass, delivering better fuel economy and torque over its light-oil predecessor. Engineering magazines of the time, such as The Engineer, were impressed by its advanced design. The machine was gradually refined and, although I have no sales figures, from what I’ve read it sold in reasonable numbers, both here and overseas.

We’re indebted to Ken Jackson, who has kindly provided access to a brochure produced by McLaren’s, promoting the Windlass. This is thought to be date for sometime during the late 1920s and early 1930s, and it’s from this publication that much of what follows originates. However, if anyone can date the brochure illustrations included here more precisely, we’d love to hear from you.

TOP: The McLaren Turning Cultivator was manufactured in three sizes – 7/9 tyne, 9/11 tyne and a 11/13 tyne. MIDDLE: The Turning Knifer was built with five tynes. BOTTOM: The Ridging Body was fitted to the rear of the cultivator frame.

General description

The Windlass chassis was of simple construction; braced steel channel with a sprung undercart supporting the road wheels. The worm-driven rear axle was fitted with a differential and ribbed drive wheels, which could be supplemented with ‘spudlets’ for additional adhesion.

The front pair, steered with a simple chain set-up, were grooved to prevent steering side-slip, and there was provision for angle-iron plates to be fitted for additional grip. Widening rings of various widths could be bolted to either set of wheels, to reduce soil compaction.

The four-cylinder, front-mounted diesel engine produced 60-70hp at 800rpm, and was started with a twin-cylinder 8hp petrol donkey engine. The diesel engine camshaft had three compression settings, ‘None’, ‘Half’ and ‘Normal’. To start, it was set at ‘None’ and, once the diesel engine flywheel was spinning at 170rpm, there would be sufficient stored energy for it to fire once the cam lever was switched to the ‘Normal’ position. At this point, the donkey engine automatically disengaged. Each engine was cooled by its own system.

A cylindrical fuel tank held both types of fuel, and was fitted with a stop cock to change the type delivered to the engines, under pressure via a hand pump.

Power for belt-driven machinery was taken from an extended crankshaft; driven via a clutch which allowed the shaft to be pulled in and out of gear while running. It also controlled the engine and ploughing gear. The vertical ploughing drum overhung the rear of the chassis, allowing for a short wheelbase and a reduction in weight.

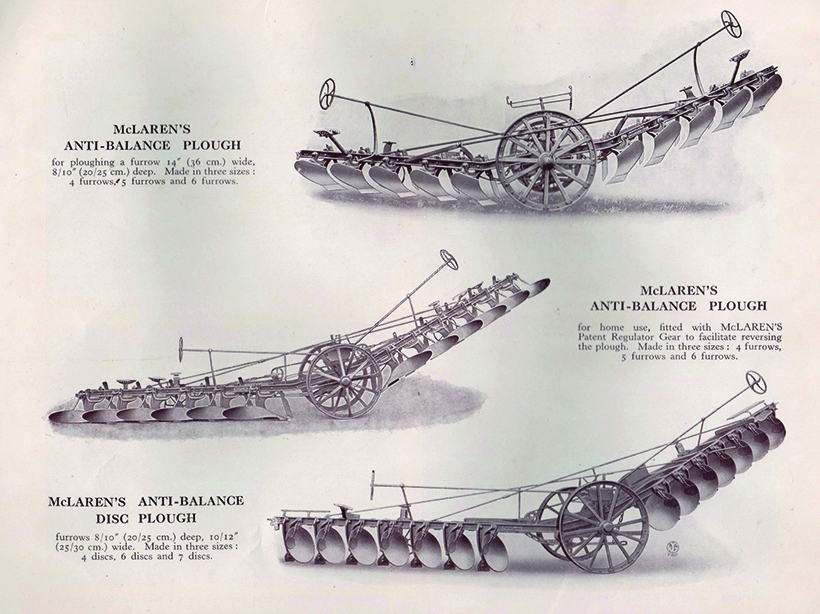

Three types of anti-balance plough. Note the plough in the bottom image is fitted with discs. TOP: For ploughing furrows 14in wide and between 8-10in deep, and made in 3-, 4- and 6-furrow configurations. MIDDLE: Fitted with patented regulator gear to reverse the plough in three sizes – 4-, 5- and 6-furrow. BOTTOM: Furrows 8/10in deep and 10/12 wide, in 4-, 6- or 7-disc configurations.

A pitch chain connected the countershaft sprocket to the main drive shafts, and sliding pinions on the shaft allowed engagement of either drive or ploughing mode. The road gear was actuated by bevel pinions and a bevel wheel on a vertical shaft to the worm drive and differential; the latter was essential for working on uneven ground, and coping with tight turns.

Both road and drum gear were safeguarded by a locking arrangement that prevented selection of multiple gears. The vertical, chain-driven winding drum was fitted to a horizontal shaft secured at either end; the manufacturer preferring this to a horizontal-type fitted to a vertical shaft with less ground clearance.

The sales brochure highlights the following advantages of ownership. In precis: ‘The machine can be placed at any angle to the field and, because the draft rope is fixed at a low level, there is less chance of side-slippage, or the rope getting tangled on the drum, such as with horizontal winding gear.’ I’m not sure I agree with this point, as the latter set-up is fine if correctly set up and professionally used.

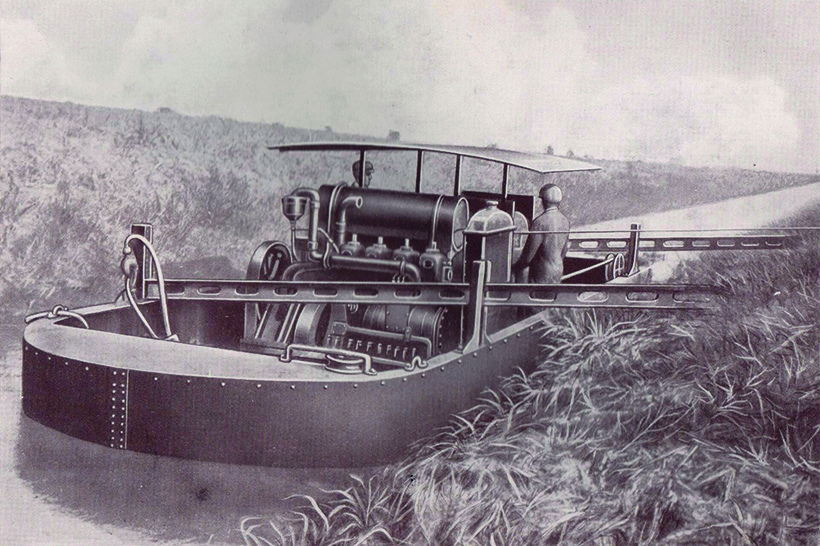

Punt Tackle and implement in use to irrigate the wetland beds. Note the extended channels projecting beyond the gunnels of the punt, to prevent overturning.

Working costs

A McLaren customer provided the following feedback from using a diesel-powered windlass to haul a three-furrow, balanced plough in heavy soils, with a 15-inch furrow. Working costs were assessed at 12d per acre, fuel was priced at 4d per gallon, equivalent to 29.6d (old pence) per hectare.

From McLarens own comparative tests, carried out over two months in Spain and excluding differing soil conditions that the above customer would have cultivated, fuel costs were assessed at 8d per gallon, with a calculated cost to work an acre of 9.41d, or 23.3d per hectare.

Perhaps more informative is the following comparison with cultivating a 10-acre plot working a 60hp, paraffin-fuelled tracked tractor pulling a 1,000kg cultivator. The model is not specified, and two windlasses, one paraffin and the other diesel-fuelled, drafting a far heavier 3,000kg model.

Patent ‘Sawah Wheels’ for use only on extremely wet and boggy land, to reduce ground pressure.

Practical comparisons

In short, the results confirm the diesel windlass completed the work in three hours, and was the most economic at 6.4d per acre, followed by its paraffin counterpart in 3.5 hours at 33.6d per acre. Finally, the tracked machine took five hours, at a cost of 55d per acre.

Although the point was made, one wonders how long it would have taken a Standard Fordson of the same period to do the same work with appropriately-weighted cultivation equipment? Neither are there comparative capital costs of the equipment, nor set-up times between steam and wheeled tractor, versus a windlass.

However, at the time, the windlass was certainly useful for deep ploughing and cultivation, but it would soon become outmoded by more powerful, general-purpose tractors that were being developed.

J&H McLaren engineered an extensive range of machinery.

Cultivation equipment

A whole variety of equipment was produced by McLaren Ltd, including cultivators, anti-balance ploughs and disc ploughs, disc harrows, balanced knifer, and mould ploughs. There were also esoteric items such as punt tackles. The windlass was mounted in a punt/boat and, instead of being positioned on the headland, was stationed floating in canals to facilitate irrigation and drainage of wetland beds. Last, but certainly not least, ‘Sawah’ wheels. One definition in the dictionary refers to Sawah as ‘wet or irrigated rice fields in Indonesia’.

The company was only too pleased to advise its clients about the most appropriate equipment for their requirements. In some countries, McLaren cultivators were used in preference to ploughs for preparing the ground, as they were found to be more efficient, given the soil conditions. Balanced and anti-balanced ploughs were manufactured, the latter with the company’s patented regulator gear, allowing one man to reverse the plough at the headland. Hard-rolled steel mould boards and renewable steel shares were carried by cast skives.

For a money-saving subscription to Tractor & Farming Heritage magazine, simply click here