Bancroft Mill Engine Museum

Posted by Chris Graham on 13th February 2021

David Vaughan visits the Bancroft Mill Engine Museum, and wonders what will become of the UK’s smaller industrial heritage sites like this in the face of prolonged, enforced closure.

Bancroft Mill Engine Museum: The main engine house which, together with the machinery and boiler house and chimney, are the only surviving original structures at the Banford Mill site in Barnoldswick.

The 120ft-tall chimney of Bancroft Mill stands out above the roof tops of Barnoldswick, as it has since the mill was opened in 1920. It was the last of 13 mills to operate in the town, and featured many of the most modern constructional and engineering standards of the time, especially in the boiler plant and engine room. Today, only the engine room, boiler room and the chimney remain, and the area around it is now a housing estate. However, since 1982 the mill engine has run again, thanks to the efforts of the dedicated members of the Bancroft Mill Engine Museum.

These are the pay pots for the mill workers, who were paid by the piece of cloth they made, from which we get the terms ‘piecework’ and ‘pots of money’.

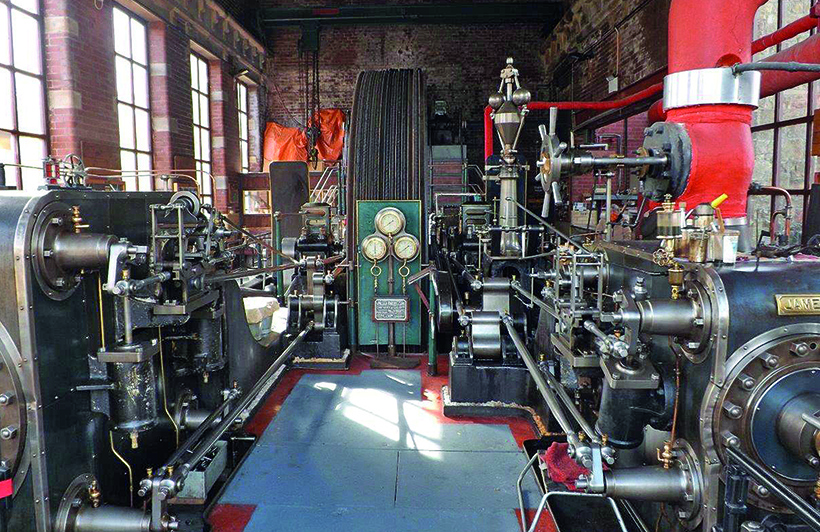

The main engine is a two-cylinder, horizontal cross-compound Corliss valve condensing engine, built by William Roberts & Sons Ltd of Nelson, Lancashire, in 1919. As recorded in 1936, the high- and low-pressure cylinders were of 17in and 34in diameter respectively, with a 48in piston stroke. The rated power was 500hp at a crankshaft speed of 72rpm. The power thus produced was sufficient to run, via a 16ft diameter flywheel and rope drive and more than 3,000ft of line-shafting, an amazing total of 1,250 looms!

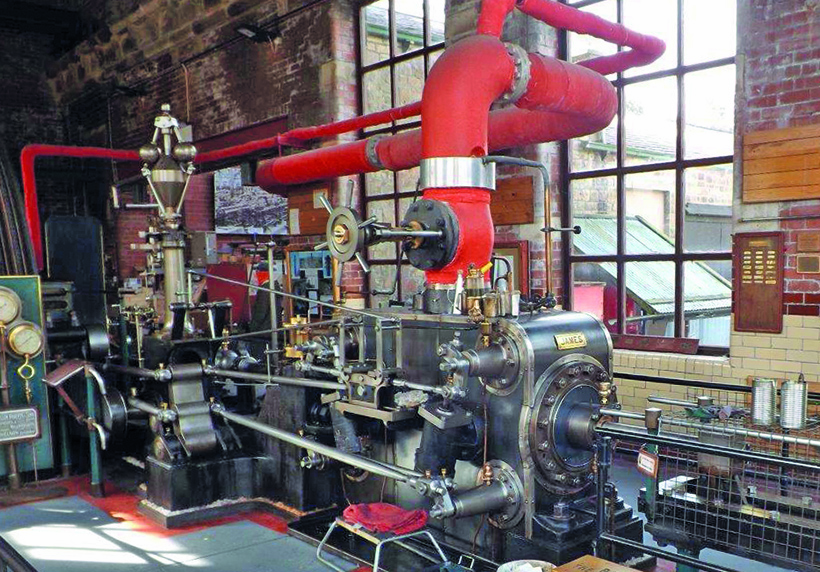

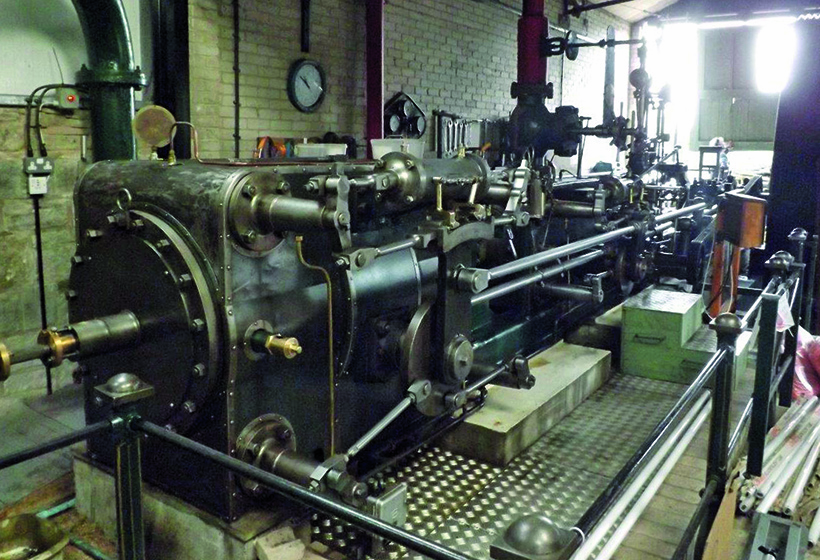

In a second shed is the so-called Bradley engine, which was rescued from a mill in Low Bradley, near Skipton. It was built by Smith Brothers & Eastwood of Bradford, in 1901, and was one of about 26 steam engines built by that firm. It, too, is a Corliss valve engine with a high-pressure cylinder of 13-inch diameter, and a low-pressure cylinder of 25in diameter. The piston has a 42in stroke. It was disassembled on its original site in 2003, then transported to Bancroft Mill. Many hours of restoration work over 14 years resulted in the engine being re-started in 2017, by regular volunteer and author, John Reid.

This is the sole surviving Lancashire loom. It was originally one of 1,250 at this mill.

The problem currently facing the mill and its dedicated team of volunteers – led by its secretary, Ian McKay – is that both the buildings housing the machinery are fairly cramped in size. Each has only one entrance and exit, and there’s no easy way of organising a one-way system of walking for visitors, so social-distancing isn’t possible. This means that the mill isn’t currently open to the public. A friend and I were fortunate to be introduced to Ian through a local volunteer, and we were made very welcome, and privileged to be allowed to look around and take some photographs on a day when other volunteers were present doing various upkeep and maintenance tasks.

A view down the engine hall, LP cylinder on right and HP cylinder on left. This shows the narrow central gangway, prohibiting traffic under current, social-distancing arrangements.

This problem is one facing many smaller heritage sites throughout Great Britain. Even larger sites, such as Beamish and the Black Country Museum, will be finding it very difficult to control on-site numbers to groups of six or less, and indoor exhibits would have to be permanently staffed, to say nothing of the numerous signs required and gallons of hand sanitiser! Yes, of course I know our health is more important, but I do wonder what the long-term effect of this ongoing situation will be for our heritage industry?

Ian McKay told me that they were able to start the engines up every now and then to keep the oil circulating, to stop corrosion and to ensure the machines are working safely and properly. They run the engines on wood which, though not as efficient as coal, is more environmentally-friendly, and is available in reasonably plentiful and cheap supply from local sources. If the mill remains closed, though, he wondered if those sources would find other outlets, and leave them without a supply in future.

The cylinders were named Mary Jane and James, in honour of the founders of the mill – James and Mary Nutter – neither of whom survived to see it completed.

Ian was also concerned that larger heritage sites, and local adventure parks, would become the normal venues for families, and that smaller sites, long closed to the public, would be forgotten by all but the die-hard enthusiast. Like all these venues, the Mill relies on its team of volunteers and, although there were several on site on the day of my visit, they were – it must be said (like myself!) – all in the older age group, and some have been temporarily lost to self-isolating and shielding.

Will they come back one wonders, and will new volunteers be attracted to these smaller sites that don’t have the charisma of a Beamish or a North Yorkshire Moors Railway? This is always a problem, but it may be further exacerbated by a prolonged period of closure.

A general view of the Bradley engine. This machine’s engine house is even more cramped than the main one, although work is in hand to improve the entrance and exit.

Ian told me that the Mill is, for the present, financially able to withstand this period of no public access, assuming that it doesn’t go on for too long. But many others are already feeling the pinch, despite some limited but welcome government support or grants. So far we have endured nine months of visitor restrictions but if, as seems likely, the situation goes on well into 2021, what will be the fate of these smaller but vital parts of our nation’s industrial heritage?

Further details are available from Bancroft Mill Engine Museum.

For a money-saving subscription to Old Glory magazine, simply click here