The brilliance of Brunel

Posted by Chris Graham on 20th February 2020

The brilliance of Brunel is celebrated at London’s Brunel Museum, which documents the great man’s first and last projects, as James Hamilton discovers

The brilliance of Brunel. A commemorative bench based on Brunel’s Tamar Bridge that connects Devon and Cornwall. The bench was commissioned in 2005.

Less than two-and-a-half miles to the east of London Bridge, on the south bank of the Thames and within the London Borough of Southwark you’ll find Rotherhithe. This is where, in 1620, the Pilgrim Fathers set off for America, aboard the Mayflower. Close to this site is the oldest surviving, Thames-side pub which, for some years has been called The Mayflower.

During the Victorian era, Rotherhithe became famous as the site of one of the most challenging engineering projects of the time; the first tunnel to successfully be constructed beneath the River Thames, engineered by Marc Isambard Brunel and his son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

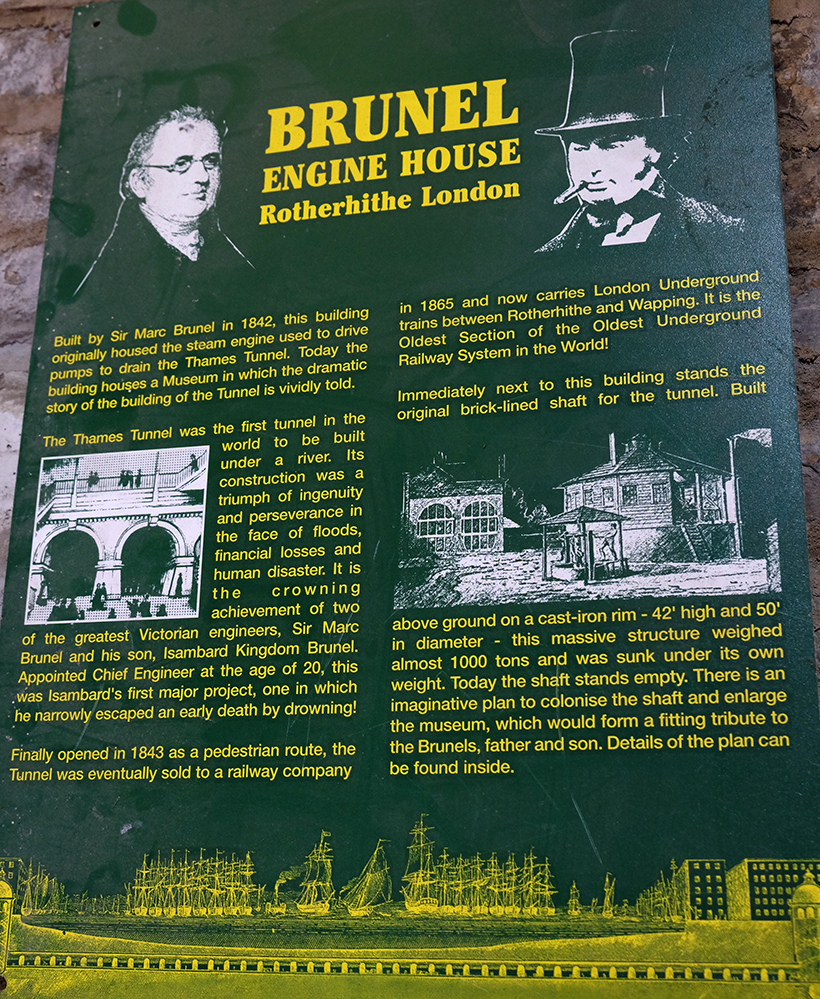

The museum building was built by Sir Marc Brunel in 1842 to house the steam engine used to drive the pumps that drained the Thames Tunnel.

The Engine House

Located in a quiet, residential area of Rotherhithe, a stone’s throw from the Mayflower pub and the Thames path, situated between Railway Road and Tunnel Road, is a brick building with a tall, red chimney. The Engine House was designed by Marc Brunel, and built in 1825 to house the steam pumping engines used to pump water during the boring of the tunnel beneath the Thames. This building is now home to the Brunel Museum, dedicated to telling the story of the Brunel dynasty through two of their projects, both with local connections; the building of the tunnel and the construction of the SS Great Eastern – IK Brunel’s first and last projects.

The exterior of the Brunel Museum Engine House and chimney.

Beside the Engine House, the walls of the cylindrical shaft rise above ground. It was constructed at the same time the Engine House, was built to access the tunnel boring and is 50ft in both diameter and depth. The workmen digging the shaft worked within a caisson, a water-tight chamber sealed at the top, which relies on air pressure to keep the surrounding water out. It’s only since 2016 that the shaft has been open to the public; for 190 years it remained closed. It’s now known as the Grand Entrance Hall, and is used as a gallery and performance space.

Looking down into the shaft, renamed The Grand Entrance Hall, and opened to the public in 2016.

The story of the tunnel’s construction is one of perseverance in the face of adversity. ‘Face’ is a particularly appropriate word, as the method of construction – devised and patented by Marc Isambard Brunel – involved the tunnelling workmen, 36 men on three levels of individual cells, digging from a supported work face 22ft high by 38ft wide. The shield was moved forward four inches at a time, as excavation and brick-lining of the tunnel progressed. It was proposed that the tunnel would be finished in three years.

Disaster strikes!

The large scale of building site was an object of fascination in itself, and became a viewing spectacle for the Victorian public. Two years into the build, Isambard Kingdom Brunel was confirmed as resident engineer. The following year, disaster struck as the waters of the Thames breached the brick-lined tunnel, and flooded in. Brunel was in the tunnel at the time and fortunate to not drown; six other men lost their lives. He was, however, injured and went to Bristol to convalesce. Work on the flooded tunnel ceased for seven years, then resumed when the treasury agreed a loan to see the tunnel completed.

There were three further floods before the tunnel finally connecting with the opposing shaft at Wapping, in 1841. It opened to pedestrian traffic in 1843, was hailed as being the eighth wonder of the modern world and quickly became an enormously popular visitor attraction. It remained as a pedestrian foot tunnel for over 20 years, but the gloss of its initial opening was dulled by the reputation the shadowy archways acquired for illicit behaviour.

The displays within the Brunel Museum Engine House.

Then, with the arrival of the railways, there came a change in the tunnel’s use. From 1865, it carried the East London Railway beneath the Thames, and this function continues to this day – London overground trains run through it. Transport for London, which runs the service, part-funded the conversion of the shaft into the Grand Entrance Hall.

Before, during, and to some degree, after the tunnel’s completion, a series of 30 drawings and watercolours were produced depicting the various stages, some by the Brunels themselves. They were displayed to the public in an arcade, before going into a private collection where they remained, largely unseen, until they came on to the market in 2017. The owning family – descendants of Brunel – put the ‘Thames Tunnel Archive’ up for sale with Bonhams.

Tunnel archive saved

The estimate price was £50,000-£100,000 for the collection, the contents of which had been highly praised for technical and artistic merit. With financial support from some major institutions, the Brunel Museum successfully acquired the collection in what it describes as ‘one of the most important moments in the museum’s history’. It represented the beginning of a new era for the museum and, at present, the precious illustrations are receiving conservation treatment to ensure their on-going condition. Hopefully, the collection will be put on public display in due course.

There has been some form of museum at The Engine House since the 1960s. However, by the 1970s, the building was falling into decay so a charitable trust was formed to save what had then been listed as a Scheduled Ancient Monument. In 1980, the restored building was reopened to the public, and renamed The Brunel Engine House Museum. In 2005, the museum was recognised as a registered museum, with a further name change to Brunel Museum.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

At the time of my visit – 2018 – it would be fair to say that things were at a transitional stage. Having successfully acquired the Thames Tunnel Archive, it’s planned to have a revamp, which will include reorganisation of the displays and improving disabled access. The volunteers are friendly and enthusiastic to impart their knowledge as they guide visitors around.

At busier times, though, they seemed a bit overstretched as they tried to deal with admissions, talking with visitors and overseeing shop sales. Fortunately, most visitors seemed tolerant, and their patience was rewarded by the opportunity to view a fascinating museum offering tangible connections to one of the greatest engineering dynasties of the Victorian era.

To subscribe to Old Glory, click here