Amazing Armstrong Whitworth stationary engine

Posted by Chris Graham on 1st November 2022

Jim Anderson reports on an Armstrong Whitworth engine (serial number 122), he bought as a 1926 7hp model with a Salmson magneto type M.1.3.

My 7hp Armstrong Whitworth engine s/n 122

Looking through my back issues of Stationary Engine, I found a reference to the Armstrong Whitworth engine in issue No. 69 (p11); when it was pictured at the 6th Aldershot Steam Rally, while in the ownership of Nick Waterfield.

More recently I’ve acquired a 3hp Armstrong Whitworth (serial number 1017). which has a pipe connecting the crankcase to the inlet manifold, giving an improved breather system.

Armstrong Whitworth history and information can be found in the Engine Torque article written by David Edgington in Stationary Engine No. 254, published in April 1995, p18-19), and again in issues 364 and 369, where a list of 16 known owners is shown.

The maker’s name on the casting.

If any fellow Stationary Engine readers have further information on Armstrong Whitworth engines, I would very much like to hear from you.

David wrote the following in Engine Torque back issue 254 (April 1995):

Brief Armstrong, Whitworth history

Following the cessation of the First World War, many factories which had been fully employed manufacturing armaments, found themselves with plenty of spare capacity. It was time to turn the production of swords into ploughshares. Many turned to agricultural implements while others viewed motor vehicles, tractors and internal combustion engines as the route to continued employment.

The serial number on the Salmson magneto.

Those interested in the study of stationary engines and their history will have noticed how many new makers and models appeared during the early 1920s; conversely you’ll also recall how many quickly disappeared.

The Armstrong, Whitworth is a typical example, coming from Sir WG Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd of Elswick, whose name held a unique place in the annals of the design development of armaments, ships, railway locomotives etc. This vast company, before the turn of the century, was called Sir WG Armstrong, Mitchell & Co Ltd; the name Whitworth replaced Mitchell following the death of Charles Mitchell, in 1895.

In 1921, when the subject of this article was launched, the other end of the manufacturing scale was involved in the production, under licence, of huge four-cylinder Sulzer two-stroke marine engines.

My recently purchased 3hp engine, s/n 1017.

The steam side was catered for by turning part of the Openshaw-based works over to the production of steam rollers, or road rollers, which were produced in four sizes (no half measures!). Other factory sites, owned by this vast concern, were involved in other diverse activities.

Designated quite simply the ‘A.W.’, the Armstrong, Whitworth (note the comma separating the two surnames) would appear to have been launched in January 1921, being listed as a petrol, paraffin or gas engine, available in sizes from 3 to 13hp.

Later information states that the three sizes which produced 3, 6, and 10hp on paraffin provided 4, 8, 13hp on petrol. Running speeds were quoted for the three sizes as 750rpm, 674rpm and 600rpm, but 100rpm adjustment (via the external governor spring adjustment spring) gave other hp ratings for special applications. Later adverts, when discussing lighting sets, also mention a 16hp size. According to the adverts it was IDEAL FOR – Farm & Estate Work, Pumping, Direct-Coupled & Belt-Driven Lighting Sets. The purchasing address was London-based, 10 Great George Street, Westminster, SW1.

Rear view of the engine s/n 1017.

Design origins & basic principles

Much thought went into the design of the ‘A.W.’ which, at first glance, looks of French or possibly Belgian descent; great consideration being given to production foolproof operation with few external moving parts.

With such vast engineering resources providing a grounding for a simple, single-cylinder, four-stroke stationary engine, we shouldn’t be surprised to see an extensively over-engineered end product just as 25 years later history would repeat itself with the Armstrong Siddeley diesel engine.

The crankshaft of the ‘A.W.’ runs in two phosphor-bronze bushes pressed into the ends of the steel crankcase. The bronze bushes are drilled to facilitate lubrication. The complex technique was usually reserved for securing aero engine or racing car gudgeon pins, enabling the bushes to be replaced at frequent intervals without affecting the main component.

Here we see the pipe connecting the crankcase to the inlet manifold, which improves the engine’s breathing system.

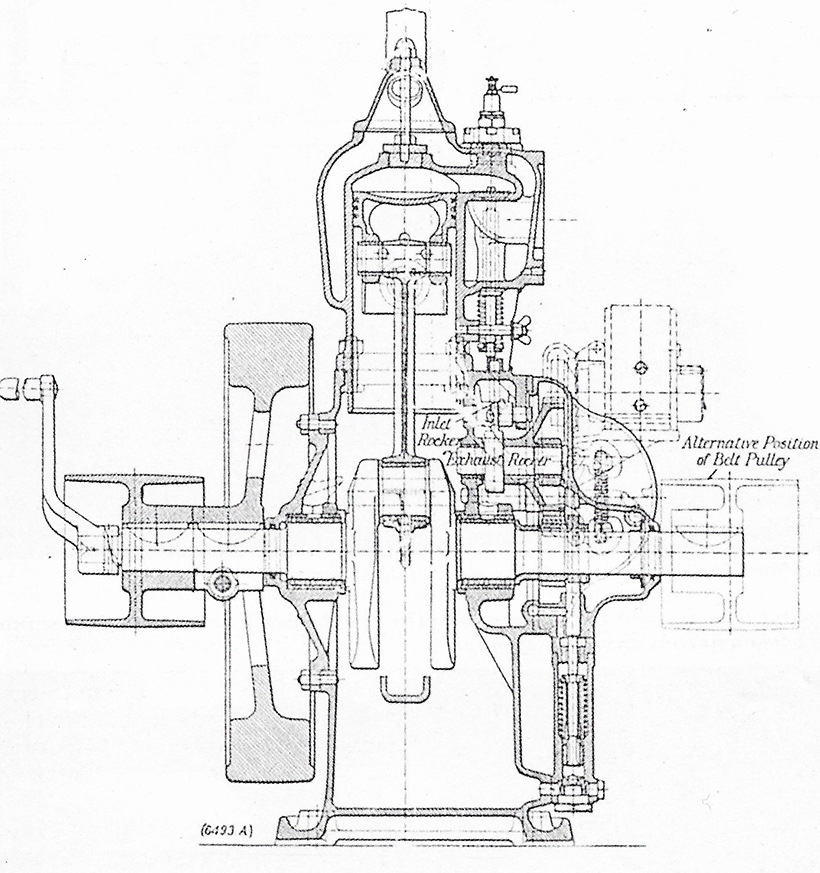

The valves, rocker, guides and other moving parts are of more than adequate size with contact surfaces being ground and hardened for longevity. The magneto is driven at full engine speed to give the hottest possible spark; naturally each alternative spark serves ignition purposes. The piston also is not of general stationary engine design (see drawing) in having a much-reduced area of contact with the liner, to reduce friction.

Although it was intended for thermo-syphon cooling by a separate water tank, a hopper could be specified at the time of purchase. This was fitted to the top facing, in place of the water connection. Does anyone have a hopper-cooled ‘A.W.’?

The vaporiser was claimed to be one of the most efficient in use. During a 44-hour test carried out at the end of 1920, less than 2% of fuel found its way into the lubricating oil.

The Drawing mentioned in David Edgington’s original article.

The ‘A.W.’ could be supplied on skids or trolley, the latter with a substantial draw-bar if required.

Survivors

Although no records exist, it would appear that fewer than 1,000 of these engines were built, a few of which fortunately, are preserved in the hands of enthusiasts.

This story comes from the latest issue of Stationary Engine, and you can get a money-saving subscription to this magazine simply by clicking HERE

Previous Post

Blakesley Show vintage working weekend

Next Post

Rare Bucyrus tracked steam shovel discovered!