Battle of the Barents Sea

Posted by Chris Graham on 15th June 2020

The Battle of the Barents Sea sounded the death knell of the German surface fleet. Allan George explains how minor actions can have major consequences.

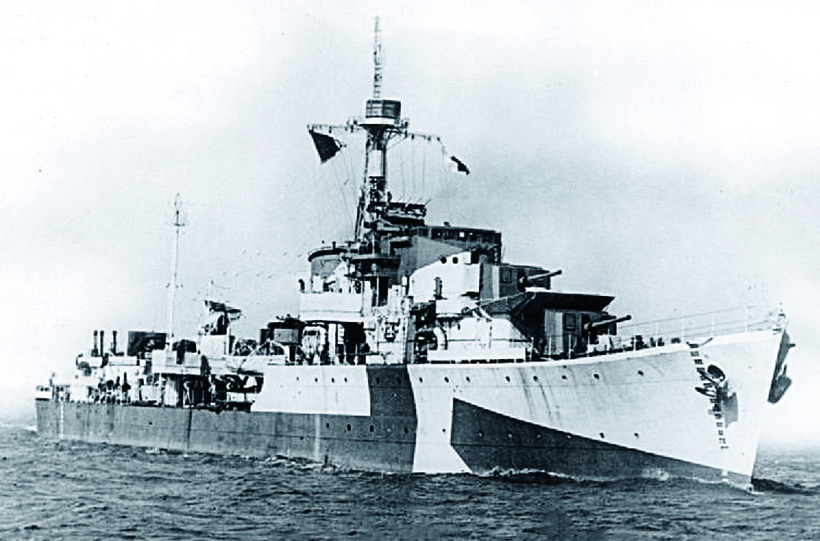

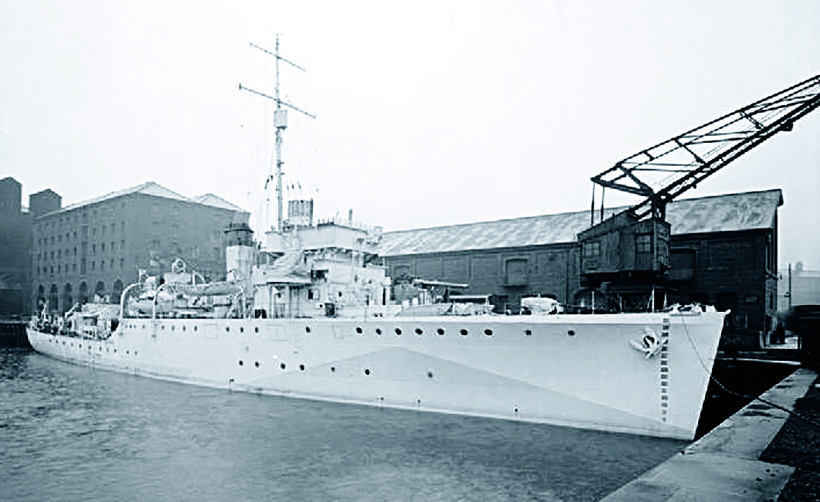

Battle of the Barents Sea: The Royal Navy destroyer, HMS Onslow.

The Battle of the Barents Sea on the last day of 1942 sounded the death knell for the German surface fleet, and saw a VC awarded to a Royal Navy captain. In the encounter, an Arctic convoy’s escorts and two cruisers fought off a much more formidable German force.

In summarising the battle, Admiral John Tovey, Commander of the Home Fleet, observed in his report: That an enemy force of at least one pocket battleship, one heavy cruiser and six destroyers, with all the advantages of surprise and concentration, should be held off for four hours by five destroyers and two 6in cruisers without any loss to the convoy, is most creditable and satisfactory.’

The RN displayed such valour throughout the action, without hesitation facing-down greatly superior forces

Captain R St Vincent Sherbrooke

that, in acknowledgement, a VC was awarded to Captain R St Vincent Sherbrooke, the senior destroyer captain.

Yet losses were actually quite light in the action, one German destroyer, and one British destroyer and a minesweeper, were sunk. The convoy itself suffered little damage, with all ships reaching port.

The Daily Telegraph stated: Despite being apparently hopelessly outgunned, the British destroyers, led by Captain R St Vincent Sherbrooke in HMS Onslow, swept in to attack the enemy squadron from the moment it was first sighted.

Four times the German warships tried to pierce the destroyers’ line to get at the merchant ships. On each occasion they failed, beaten by Captain Sherbrooke’s brilliant tactics. Finally the enemy fled – when British reinforcements, in the form of heavy ships, arrived.

But the German Navy’s failure to cause serious damage to the convoy so incensed Hitler, that it provoked him to order all warships larger than destroyers to be scrapped, leaving his U-boats to continue the offensive at sea.

Although this order was cancelled in practice, there was only one further sortie by heavy, German warships, and that ended with the sinking of the battlecruiser, Scharnhorst.

Russian convoys

To put the action into context; to help sustain the Russian forces fighting for their lives in a massive campaign against the Germans, it was vital the supply convoys got through.

For the Germans, it was equally critical to halt the stream of supplies coming from Great Britain and across the Atlantic. However, the Arctic convoys provided the most direct means of getting the armaments to the Russians, so they became the prime target for the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe in Norway.

Hitler demanded vigorous action from his navy to attack and halt the convoys. But he’d also contradicted himself by ordering his commanders to show great caution in attacking forces of equal strength, not wanting to risk capital ships. This paradox must inevitably have caused confusion, loss of initiative and perhaps hesitation in the minds of his naval commanders, and cautious admirals tend not to win battles.

Convoy JW51B

At the turn of the year, when the battle was fought, the convoys had an advantage; the Arctic night. Daylight hours were short, thus constraining air operations. But because of pack ice, convoys were forced to sail within 150 miles of the North Cape, on the Norwegian coast.

The 14 merchant ships of Convoy JW51B, carrying more than 100 aircraft, 2,000 vehicles, 200 tanks, aviation fuel and other essential supplies, were steaming from Loch Ewe in Scotland to Kola Inlet ports, primarily Murmansk. They were escorted by destroyers, corvettes, a minesweeper and trawlers. In addition, the two cruisers of Force R – Sheffield and Jamaica, commanded by Rear Admiral Robert Burnett – were standing by to the east of the convoy’s route.

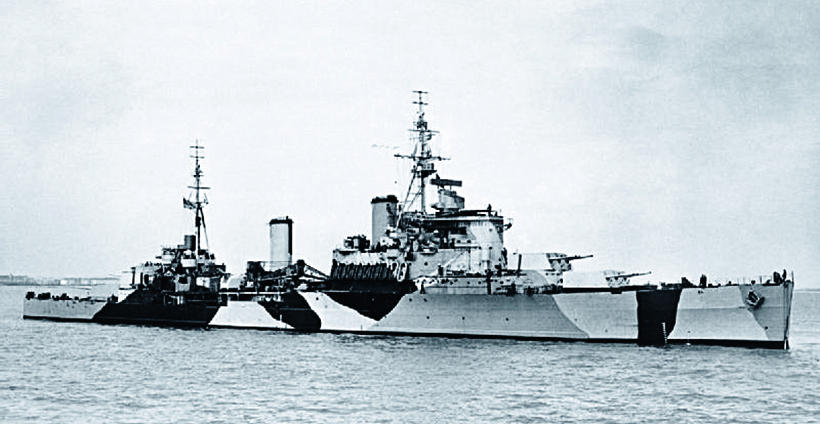

Royal Navy cruiser, HMS Sheffield.

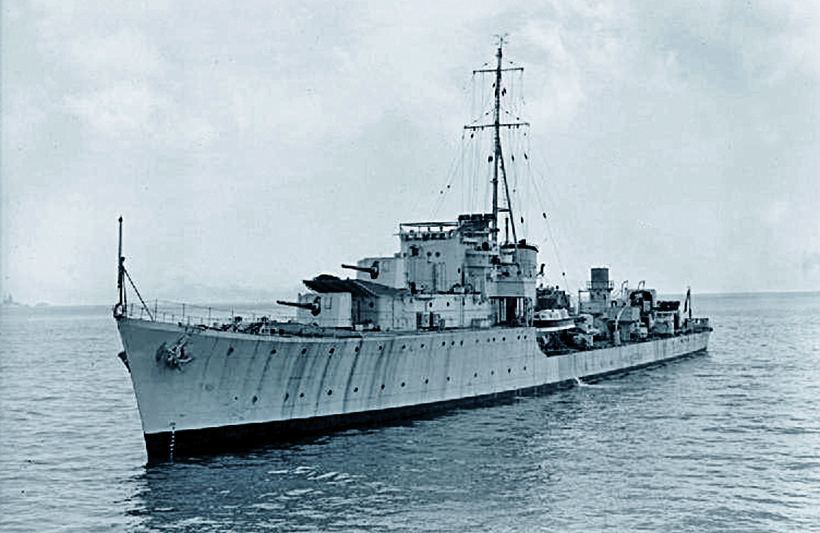

Unfortunately, heavy weather caused the merchant ships to lose station and inadvertently scatter. Then, when finally the weather moderated and the convoy gathered together again, five ships were unaccounted for, along with the destroyer Oribi and the anti-submarine trawler Vizalma. Bramble, a Halcyon-class fleet minesweeping sloop, was detached to find these ships.

The destroyer, HMS Oribi.

However, a patrol line of four U-boats lay in wait astride the track the convoys normally followed. One of the submarines, U354, sighted the convoy and reported its presence.

When the German Naval Staff received the U-boat’s report, it ordered Admiral Kummetz, who commanded German naval forces in northern Norway, to sortie out, intercept and attack the convoy.

Kummetz had a plan ready for attacking the convoy called Operation Regenbogen (Rainbow), which envisaged splitting his forces into two battle groups, each attacking a different flank of the convoy.

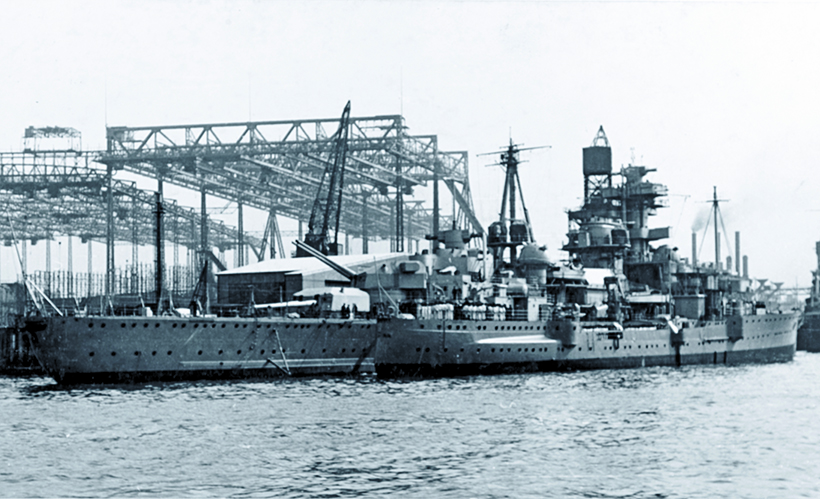

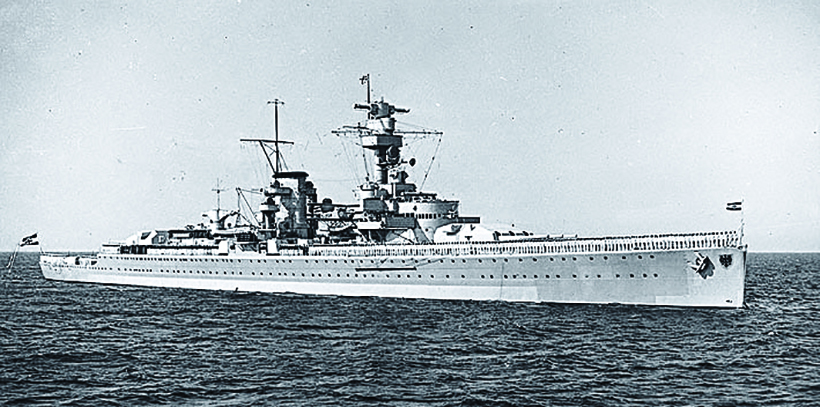

He led one battle group in the heavy cruiser, Hipper, with three destroyers. The other group consisted of the panzerschiffe (pocket battleship) Lutzow, also with three destroyers.

The German heavy cruiser, Hipper.

The official British history – The War at Sea 1939-1945 – explains the constraints upon Kummetz. His orders stated he: ‘Must not accept action with equal or superior forces, nor risk his heavy ships in a night battle in which the British escorts might use their torpedoes. The German Naval Staff, though no doubt pressed in that direction by Hitler, seems to have shown remarkable aptitude for depriving its sea-going commanders of all initiative.

But, apart from the effect of these cramping restrictions, the German plan lacked singleness of purpose; for the Lutzow was under orders to break out into the Atlantic after the attack on the convoy, and this may well account for the marked timidity with which she was handled in the fighting.’

The engagement

When U354 identified the convoy, the British commanders were struggling to gather the scattered merchant ships and escorts back into an organised group, and someships had yet to rejoin. Furthermore, the pervading Arctic gloom and frequent sleet squalls, made the hunt for the missing ships an extremely challenging task. Low visibility made it virtually impossible to see ships, other than perhaps for a few fleeting moments.

Nevertheless, by about 0800 on December 31st, some sort of order had been established, and the convoy now formed of 12 merchant ships and eight escorts, was 120 miles north of the Norwegian coast, steering east.

The minesweeper, HMS Bramble.

Bramble, one of only two ships in the escort fitted with radar, continued to search for stragglers, about 15 miles astern of the convoy. At this stage, the two cruisers of Force R were positioned 30 miles north of the convoy.

To add to the concerns of the British commanders, they knew a UK-bound convoy, RA51, had left Russian ports, and was about 150 miles to the east and steaming towards them. They were also acutely aware that, should the enemy sortie out, the low visibility and lack of radar would make any encounter a confused affair and difficult to manage.

Hipper, with its accompanying three destroyers, had crossed the wake of the main body of the convoy, and was now closing from the north. Lutzow, also with three destroyers, was approaching from the south, thus allowing the Germans to attack on both flanks of the convoy. At 0800, the German destroyer, Friedrich Eckholt, signalled Hipper she’d sighted the convoy.

Between the sleet squalls, HMS Obdurate glimpsed enemy ships, later identified as the Hipper group, astern of the convoy. She immediately steered towards them, followed by Onslow, Orwell, and Obedient. Achates and the other escorts were ordered to stay close to the convoy and obscure it by making smoke.

Admiral Burnett commanding Force R, having been warned by Captain Sherbrooke of the impending attack, turned Sheffield and Jamaica towards the enemy, and worked up to 31 knots.

Royal Navy cruiser, HMS Jamaica.

Destroyers attack the Germans

Captain Sherbrooke, at the convoy conference prior to sailing, had explained his tactics for dealing with enemy surface forces. He planned for the fleet destroyers to concentrate as a flotilla on the threatened flank, and keep between them and the merchant ships, while the remaining escorts would lay smoke.

Captain Sherbrooke’s immediate tactic was to close the Hipper group and feign a torpedo attack, hoping he could bluff the Germans into retiring without actually having to expend his most formidable weapons. For a while, this ruse worked, perhaps because Admiral Kummetz cautiously obeyed Hitler’s command not to endanger his heavy units.

But the bluff didn’t last, Hipper returned and engaged the destroyers with her main 8in guns, initially firing erratically but, eventually, she found Onslow’s range. The destroyer withstood a number of hits which caused considerable damage. Her engine room was set on fire, 17 sailors were killed and many others injured, including Captain Sherbrooke, who was struck by a shell splinter, causing him to lose an eye.

As a result of this injury, he passed command of the destroyers to Lt Cdr DC Kinloch, of Obedient, who coincidentally was promoted Cdr on New Year’s Eve, 1942, actually during the battle.

Now steaming to the north of the Convoy, Hipper encountered Bramble, which opened fire with her two 4in guns, against Hipper’s eight 8in, and 12x 4.1in guns. The inevitable outcome of this unequal contest was the loss of the minesweeper with all hands.

Vectoring Force R’s cruisers by wireless towards Hipper, Kinloch disengaged and took the destroyers back towards the convoy.

At 10.45, the corvette Rhododendrum identified enemy ships to the south of the convoy, the Lutzow force. Apprehension, and a passing snow storm, caused Lutzow’s captain to hesitate and not attack the largely helpless merchant ships immediately. This timidity saved the convoy from disaster.

The pocket battleship, armed with six, 11in, and eight, 5.9in guns, with its destroyer escort, had come within a few miles of the convoy, before turning away, apparently waiting for the weather to clear. An example of the excessive caution created by Hitler’s order.

By 11.00, the destroyers had rejoined the convoy and placed themselves between it and the Lutzow force. Meanwhile, Hipper came up to Achates, and engaged the destroyer, quickly crippling her, causing many casualties including her Captain, who was killed.

Hipper subsequently opened fire on Obedient, but the threat from the destroyers’ torpedoes caused the heavy cruiser to veer away.

Force R’s cruisers arrive

As Hipper changed course, the Force R cruisers which, unbeknown to her, had closed the range, engaged with heavy gunfire.

Hipper received several hits which reduced her speed slightly. She turned away making smoke, and Admiral Kummetz ordered all his ships to disengage and retire to the west.

However, at about 11.45, two of the German destroyers appeared about 4,000 yards from the Force R cruisers, in an ideal position to launch a torpedo attack. Sheffield opened fire upon them, swiftly reducing Friedrich Eckoldt to a sinking wreck. Jamaica fired at the other destroyer, which turned away.

At much the same time Lutzow opened fire on the convoy with her 11in main armament, damaging one merchant ship. The British destroyers again steered towards the pocket battleship and laid smoke.

The German ‘Pocket Battleship’, Deutschland, which was renamed Lutzow, in 1939.

Admiral Kummetz made one more attempt in Hipper to reach the convoy, but the British destroyers steamed towards him and themselves came under accurate fire. However, the German Admiral didn’t persist, simply repeating his order to retire.

Achates, now in a parlous state and close to sinking, continued to shield the convoy with smoke. Eventually, at 13.45 she called for assistance, and capsized as a rescuing trawler approached.

The Force R cruisers opened fire on the retreating German ships, although not causing any damage, and Admiral Burnett pursued them until he lost contact at about 14.00.

Subsequently, four of the five merchantmen and one escort actually rejoined the convoy, with the final missing merchant ship and escort arriving at the Kola Inlet independently.

The outcome

The convoy reached Russian ports in the Kola Inlet without further mishap. A British destroyer and minesweeper, and a German destroyer were sunk. But of much more significance was the impact the action had upon the Germans.

It had been planned that Lutzow would continue into the Atlantic for a commerce-raiding foray, but this was cancelled. Hipper was out of action for a period while her battle damage was repaired.

But of greater consequence than the material damage, was the rage the ineffective action produced in Hitler. He was so incensed at what he perceived to be a powerful force being driven off with such apparent ease, that he declared his unalterable resolve to scrap all vessels larger than destroyers. His hour long rant at Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, Head of the Kriegsmarine, led to Raeder’s resignation and replacement by Admiral Karl Donitz, commander of the U-boat fleet.

Hitler’s naval aide, Vizeadmiral Krancke, observed that the scrapping policy would be the cheapest victory Britain could possibly win. Actually, the heavy ships weren’t scrapped: Donitz eventually persuaded Hitler, who with bad grace agreed, they had a deterrent value as a fleet in being. Nevertheless, there was only one further sortie by a heavy German ship, the Scharnhorst, which led to her sinking.

Allied Arctic convoys continued sailing and supplies were kept flowing to Russia, but now attacks came from just U-boats and the Luftwaffe.

VC AWARDED

Captain Robert St Vincent Sherbrooke, a descendant of Admiral of the Fleet, John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent, victor of the Battle of Cape St Vincent in 1797, was awarded the Victoria Cross for his part in the action. However, he acknowledged it had been awarded for his crew.

He lost the sight of one eye as the result of the severe wounds he suffered in the action. Nevertheless, he returned to service and retired from the RN as a Rear Admiral.

Buy a money-saving subscription to any of Kelsey Publishing’s transport magazines, by clicking here